There were two main reasons I wanted to test Heaven 11’s Billie integrated amplifier-DAC in my current System One. First was its reasonable price: $1450 USD. The other, far more important reason was how much careful consideration seemed to have gone into so many aspects of its design. This is a product -- and a company -- that began life as a Kickstarter project. Now that those Kickstarter pre-orders have been filled, the Billie is available for sale at Heaven11Audio.com, backed by a 30-day money-back guarantee and a five-year warranty.

Description

First, a bit about the names of this model and this brand. In late July, when I spoke with Heaven 11’s founder and industrial designer, Itai Azerad, in his office in Montreal (see my August “Opinion”), he told me that he’d named his brand Heaven 11 because he liked the sound and rhythm of the phrase. The Billie’s name is a nod to American jazz singer Billie Holiday (1915-1959), who made her first recordings at the age of 18: “Your Mother’s Son-in-Law,” backed with the hit that sent her to stardom, “Riffin’ the Scotch.”

The names were just the start. Azerad told me that when he dreamed up the Billie, he knew that, if it was to be successful, he had to make it stand out from the crowd -- a décor-friendly product that anyone would be proud to show off as the centerpiece of a living-room stereo system. He wanted its feature set to be useful to both audiophiles and modern-day listeners. Of course, he also wanted it to sound good -- and he wanted to make it entirely in Canada.

He seems to have fulfilled all of those dreams, and then some. The Billie is not only made in Canada, it was entirely designed in and is manufactured in and around Montreal.

Being an industrial designer, Azerad took control of the Billie’s looks, functions, and manufacture. His most noticeable contributions to the amp’s appearance are the hand-crafted wooden knobs on its faceplate -- a big one for volume control, a little one for input selection and muting -- as well as having the tubes rise naked through the top panel. Wrapping a folded-metal chassis is a similarly folded case of brushed aluminum, in silver or black, made of a single piece of 1/4”-thick, extruded aluminum and comprising the front, top, and rear panels. The top of the case is engraved with Heaven 11’s logo, just in front of the tubes; the “11” of the logo is also engraved next to the volume knob. The overall design more than hints at artisanal luxury, primarily because of the wooden knobs -- Azerad said he chose them because variations in grain and color mean that no two knobs look the same.

I asked Azerad how he was able to use the aluminum piece and keep the price so low. He told me that the case is made from a commonly available aluminum extrusion with a C-shaped cross section measuring 8” x 2.75”, a size used in many industrial applications and so easy to obtain. C-channel extrusions are made in very long lengths; once he’d found the right supplier, he just needed to have the extrusion cut into lengths of 14.25” -- the Billie’s eventual width -- and have the pieces finished. (The Billie’s overall dimensions are a predictable 14.25”W x 2.75”H x 8”D, excluding tubes.) He’s also produced a fancier version, the Billie Heaven’s Angels Limited Edition ($1650), of which only 11 will be made. Otherwise identical to the standard Billie, it has matched tubes and top panel decorated with hairline laser etching -- Azerad calls the result a “Spirograph-inspired play/riff on the Heaven 11 logo.”

Azerad is not an electrical engineer. Originally, Robert Lefebvre, from the Montreal area, helped out with the design of the prototypes, but to come up with the final production version Azerad turned to two other Montreal-area designers, Denis Rozon and Sylvain Savard. Rozon designed the preamplifier section, which uses the Billie’s two JJ ECC99 tubes. Savard designed not only the power-amplification section, which uses ICEpower class-D modules to generate up to 60Wpc into 8 ohms or 120Wpc into 4 ohms, but also: the phono stage (moving-magnet only); the digital section, whose core is an ESS ES9018K2 DAC chip; the headphone amp (there’s a 1/8” jack on the front panel); and pretty much everything else that involves an electrical signal.

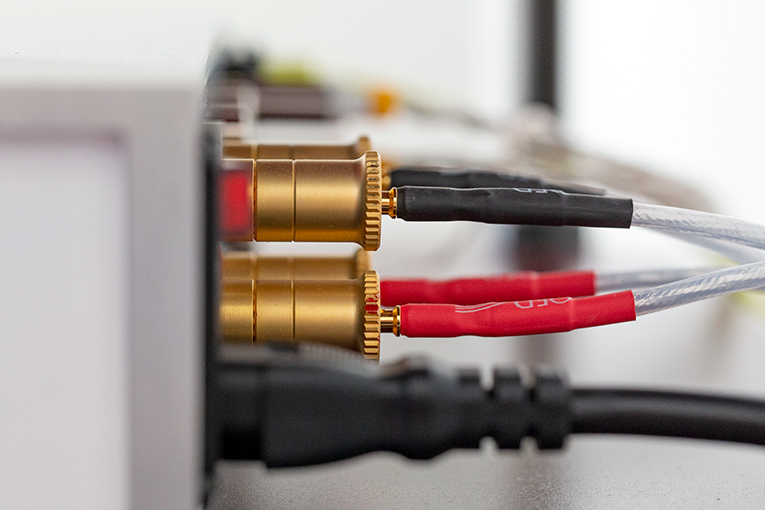

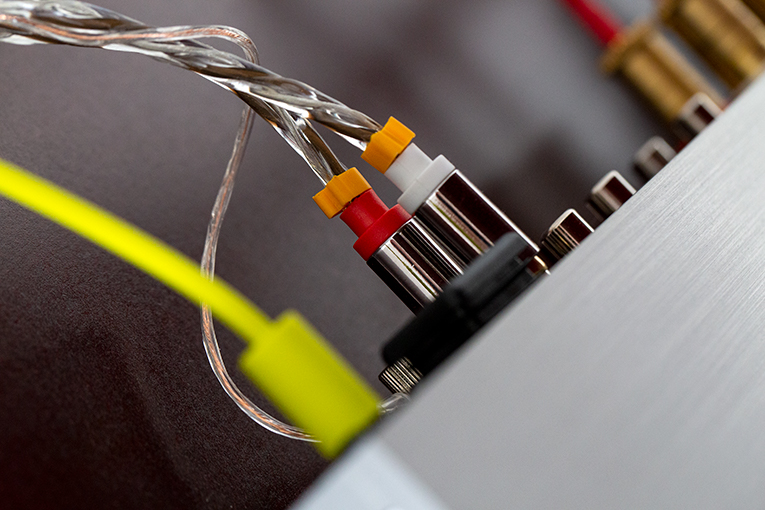

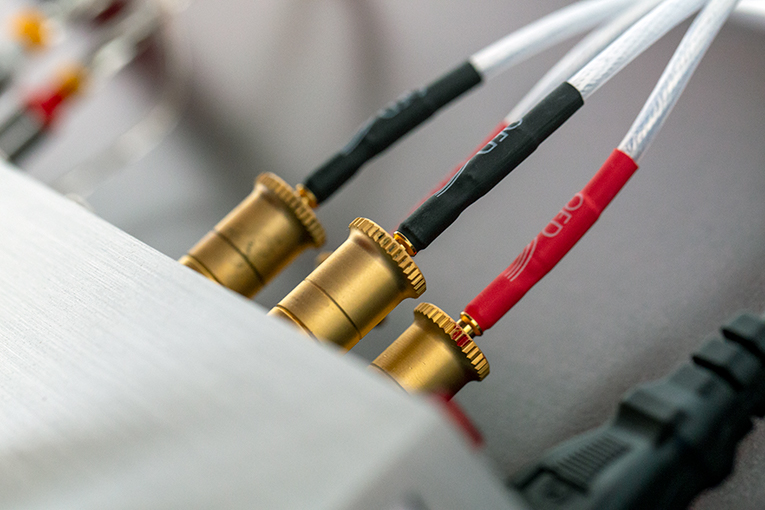

On its rear panel are, starting at the right end, two digital inputs (TosLink); three left/right pairs of analog inputs (RCA) labeled Aux 1, Aux 2, and Vinyl; a ground post for a turntable; and left/right Line Out (RCA) outputs to connect to a subwoofer or for preamp-only use. Between the phono and TosLink inputs is a small raised rectangle of plastic -- this is the Bluetooth antenna, for wireless but lossy digital connection (the aptX, AAC, and A2DP codecs are supported). Near the left end of the rear panel are sturdy, all-metal speaker terminals, a main power rocker switch, and a three-bladed IEC inlet for the included power cord.

The top and front panels are spare -- those wooden knobs, the headphone jack, and seven narrow slits through which glow indicator LEDs, mostly orange. But a lot of work has gone into things that aren’t at first obvious. For example, there are also orange LEDs under the tubes -- when the power rocker is flipped on, these flash for 30 seconds as the tubes warm up, then go dark, indicating that the Billie is in standby. There’s no separate On/Standby control on the front; instead, when the volume knob is turned clockwise from its full-off position (i.e., when the flat part of the knob is level with the top panel), the amp turns on. Turn the knob counterclockwise to shut the Billie down.

The only thing I didn’t like about the Billie’s operation is it needs to be manually turned off. This is unlike NAD’s D 3045 ($749) or Audiolab’s 6000A ($949.99) integrated, both of which have been part of past Systems One -- those models automatically shut themselves down after 30 minutes of idle time, which I like and had gotten used to (in many countries, auto turn-off is mandatory in amplifiers). More than a few times, I forgot and left the Billie on for hours, or even days. No real harm done -- but I might have diminished the tube life by a bit.

The input-selector knob -- pressed instead of turned, it does double duty as the Mute knob -- has LEDs of its own. The row of six parallel slits on the top panel, just above the knob, correspond to the order of the inputs on the rear panel. When the knob is turned left or right, the LED corresponding to the input selected glows brightly, and a second later dims to indicate full engagement. All LEDs glow orange except the third from the left, for the Bluetooth input, which glows blue when unpaired with a Bluetooth device, then orange when pairing is complete. I found the Bluetooth input handy -- I used it and a Samsung Galaxy S10 smartphone to listen to podcasts and audiobooks -- but I didn’t use it for critical listening.

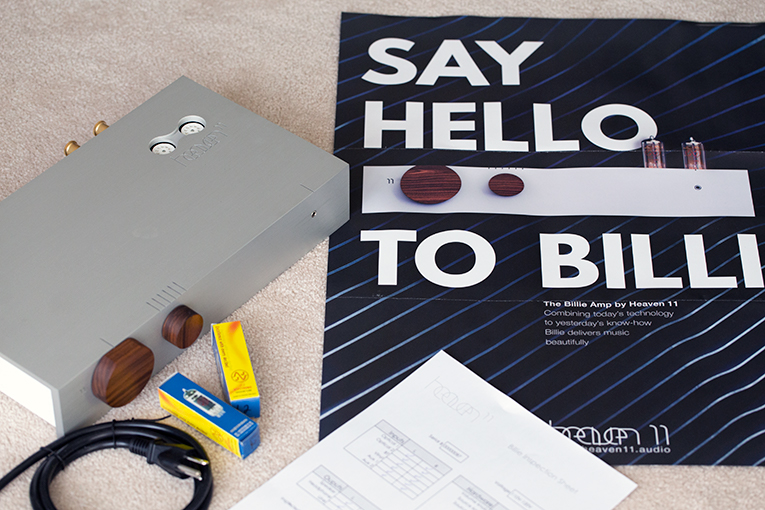

All in all, I found the Billie well thought out, and it arrived in well-thought-out packaging. I opened its white shipping carton to find the amp protected by big pieces of Styrofoam. Instead of an instruction manual, a double-sided poster headlined “let’s play” presents all the information needed to quickly get the Billie up and running. A quality-control checklist is supplied to confirm that your unit was checked before it left the factory. Still, the Billie is not entirely plug’n’play -- the tubes must be removed from their boxes and inserted in their sockets, which is easier than screwing in a lightbulb. Typically, the tubes last about 3000 hours; replacements can be had for less than $20 each.

Setup

I connected a Chromecast Audio wireless streamer ($35, discontinued), using its partnering TosLink interconnect ($10, discontinued), to one of the Billie’s TosLink inputs, so I could wirelessly stream uncompressed music from Tidal. I attached a Pro-Ject X1 turntable to the phono input, using the X1’s supplied phono cable. (In the US, the X1 sells for $899 bundled with a Sumiko Rainier MM cartridge; mine is the European version, which sells for €799 with Pro-Ject’s Pick It S1 MM cartridge.) I used the Billie’s stock power cord.

Loudspeakers were Paradigm’s Monitor SE 3000F ($698/pair), which I wrote about in July, and Wharfedale’s Linton Heritage ($1498/pair with stands), which I wrote about in October. At first I used AudioQuest Q2 speaker cables ($179/10’ pair) with both pairs of speakers, but then switched to QED XT25 cables ($84.99/2m pair), which are now my System One staples -- no change in sound, but a big reduction in cost.

Sound

As I wrote last month, when I compared the Paradigm Monitor SE 3000Fs to the Wharfedale Linton Heritages, the speakers sounded quite different. When I drove them with the Billie, I noticed some things they had in common.

First, the Billie was powerful enough to drive both pairs of speakers to high volume levels, even with the sort of bass-heavy music that can tax an amp’s reserves. As described last month, I used the Billie to torture-test the Lintons with music from yet another Billie. At stupid-high volumes I played “Bad Guy,” from Billie Eilish’s When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go? (16-bit/44.1kHz FLAC, Interscope/Tidal), to see if the speakers could handle it. I heard no distortion from speakers or amp, and, from what I could tell, I was nowhere near taxing the Billie’s limits -- the dynamics sounded unrestrained, and the sound remained clear throughout the audioband. The Monitor SE 3000F is less sensitive than the Linton Heritage, but with the Billie, deafening output levels were a cinch with either speaker. Sixty watts per channel into 8 ohms isn’t all the power in the world, but most people shouldn’t need more, as long as their rooms aren’t too big and their speakers are efficient.

The Billie was reasonably quiet, but not overly so -- with one of my ears within a foot of a Paradigm or Wharfedale tweeter, and no music playing, I could hear a slight buzz, a hint of hum, and a subtle shhhh. The Billie was a little noisier than the Audiolab 6000A, which it had just replaced. Then again, I never expect any tubed product to be all that quiet. Even the very costly tubed gear I have makes a lot more noise than comparable solid-state gear. I can forgive the Billie’s small amount of noise -- especially because it was masked by any music I played, even at low volume.

With both speakers, I found the Billie’s sound clean and, probably because of its tubed preamp section, slightly smoother and warmer than the Audiolab 6000A’s, which in my various Systems One has sounded a little cooler through the mids and slightly sharper in the highs. The Billie could generate a pretty robust sound while still sounding refined. For example, playing through the 3000Fs “Los Ageless,” from St. Vincent’s spectacular-sounding Masseducation (16/44.1 FLAC, Loma Vista/Tidal), proved that the Billie’s reproduction of a piano could be big and rich, even as its portrayal of St. Vincent’s voice was smooth and detailed. I love this song’s chorus: “How can anybody have you and lose you / And not lose their minds, too?” As St. Vincent, aka Anne Erin Clark, sings these words, the pain is evident in her voice and inflections. The Billie revealed it all -- everything was clearly audible and felt emotionally immediate.

That digital playback sounded very good through the Billie didn’t surprise me -- digital has evolved to the point that, these days, any differences in sound between the lowest- and highest-priced digital-to-analog converters are often very small.

The sound of LPs through the phono stages of inexpensive integrateds can be hit-or-miss, but the Billie’s phono stage took me aback. With the Paradigm 3000Fs still hooked up, as soon as I lowered the stylus into the lead-in groove of side 2 of Bruce Springsteen’s Tunnel of Love (LP, Columbia COC 40999), which begins with the title track, I knew I was in for a treat -- the sound was clear throughout the audioband, with superstrong bass, startlingly pure highs, and dynamics that were every bit as pronounced as the Billie’s digital playback. Part of that had to do with the turntable -- Pro-Ject’s X1 punches well above its weight with a bold, clean, powerful sound -- but kudos to the Billie for not holding it back.

Excited by how LPs sounded with the Billie driving the Paradigms, I ran upstairs to my record boxes and dug out more. Next up was the Queen City Kids’ Black Box (LP, Epic PCC-80065), a 1982 album by a little-known Canadian band from the city I mostly grew up in, nicknamed the Queen City because, when founded in 1882, it was named Regina, in honor of Queen Victoria. Black Box was recorded in an abandoned bank in Winnipeg, Manitoba, to capture the sound of a rock band recorded “live in the studio” in a large acoustic space. Sonically, the result is a bit of a mess -- the instruments and voices don’t come across clearly, probably because of that big, reverberant space. But for a rock recording, it sure sounds spacious. I heard again the bold, incisive sound I’d heard with Tunnel of Love, and it was dead easy to hear the sense of space around the players.

Next up was a far-from-pristine 1977 pressing of Steely Dan’s Aja (LP, ABC 9022-1006). Despite the abundance of surface noise, “Cowbell” sounded punchy, spacious, and really alive. I was thrilled. But by then I knew I had to do a bit of a recalibration by returning to the TosLink input I’d plugged the Chromecast Audio into. I then streamed “Cowbell” from Tidal, to hear what its digitized version sounded like through the Billie. In two words: quite different. First and foremost, the LP’s surface noise disappeared, as you’d expect. But the Tidal stream also had tighter bass that went slightly deeper, as compared to the LP’s rounder, more textured bass -- the former sounded more authoritative but somewhat closed in, the latter a little richer and more natural. The Tidal stream’s highs were a bit cleaner, but the LP’s were a little more spacious, which allowed the soundstage to fill the room more. I assessed the midrange mostly with voices. With the LP of Aja I had to listen more closely to hear the voices clearly -- they sounded a bit recessed, which made me want to turn the volume up. With the Tidal stream, the voices were just a little more present, even at very low volumes.

Neither format was a decisive overall winner -- each had pros and cons. Furthermore, this informal comparison shouldn’t come across as a condemnation or approval of vinyl or digital playback -- the provenances of these recordings, completely unknown to me, probably account for some or most of the differences I heard. All I can tell you is that they both sounded very good overall, and that with the Billie you can enjoy analog and digital playback equally -- it seemed to shortchange neither format.

Unfortunately, I was as unimpressed with the Billie’s headphone output as I’d been impressed with its phono stage. Still playing the Aja LP, I plugged in a pair of PSB M4U 2 headphones switched to their passive mode (i.e., with their internal amplifiers turned off). The M4U 2s have been criticized for sounding too fat and heavy in the bass, but now they sounded like three-way speakers with the woofers turned off -- all highs and midrange, no bass. I turned the Billie’s volume control way down, enabled the M4U 2s’ internal amps, and played Aja again. There was more bass this way -- but also more noise from the M4U 2s’ circuitry.

Something seemed awry. Still playing Aja, I plugged a pair of NAD HP20 earphones into the Billie and heard the same thing: tinny sound with no bass. I grabbed my younger son’s cheap Sony over-ear headphones, plugged them into the Billie, and heard more bass than with the PSBs or NADs, but it was still weak.

To make sure that Aja itself wasn’t to blame, or the phono input and how it works with the headphone output, I streamed from Tidal the title track of J.S. Ondara’s Tales of America (16/44.1 FLAC, Verve Forecast), which has a strong, prominent bass beat. Again, the M4U 2s sounded like wooferless three-ways. Then I tried my wife’s pair of Pryma 01 headphones -- the bass wasn’t as absent as with the PSBs, but there still wasn’t enough of it. Finally, I successively plugged the PSBs and Prymas directly into my Samsung Galaxy S10 smartphone, which I’d been using to control the Tidal stream. Driven by the phone, both headphones produced much deeper, richer bass, and sounded just as clean through the rest of the audioband. I can’t recommend the Billie’s headphone amplifier.

Verdict

If Heaven 11’s Billie were a dedicated headphone amp, Houston, we’d have a problem. But for me, its headphone output is the least essential of the Billie’s features -- I mostly use my phone for headphone listening. That deficiency does little to reduce my respect for what Itai Azerad has achieved in the Billie.

I like its styling and build quality, and its sound through speakers, whether playing digital files through one of its TosLink inputs or LPs through its MM phono stage. That latter assessment is critical -- vinyl is hot these days, and the Billie’s phono stage sounds good enough that it’s easy to imagine someone who values a component’s appearance and sound partnering it with a good turntable (e.g., Pro-Ject’s X1), a pair of great speakers (the ones I used, or many others), and have a thoroughly pleasing-sounding, great-looking system for years to come for what is a very reasonable price.

It’s one thing to be a big company that can take advantage of economies of scale and/or Asian manufacture to crank out good-sounding, high-quality audio gear, like many of the components I’ve featured in this column. It’s quite another to be, essentially, a one-man operation producing, in Canada, a bespoke-type product like the Billie for only $1450. I’m surprised Azerad has pulled it off. The Billie is an auspicious debut for Heaven 11 -- and I suspect it’s only the prelude to much more from this innovative Canadian brand.

. . . Doug Schneider

das@soundstagenetwork.com