Every year at the Oscars, there’s a film tribute for the motion picture industry notables who passed away in the previous year. Inevitably, they leave out one or two, probably through human error, but I suspect because of politics, too; one can only imagine if they’ll include Harvey Weinstein, Bill Cosby, and the like, once they shuffle off to whatever level of Dante’s Inferno awaits them.

Every year at the Oscars, there’s a film tribute for the motion picture industry notables who passed away in the previous year. Inevitably, they leave out one or two, probably through human error, but I suspect because of politics, too; one can only imagine if they’ll include Harvey Weinstein, Bill Cosby, and the like, once they shuffle off to whatever level of Dante’s Inferno awaits them.

That said, I’m in a woefully contemplative mood because of the recent passing of one who certainly is destined for the other place. By now, everyone in the industry knows that we lost Dave Wilson after his battle with cancer. And fight he did: Dave was of such an enquiring bent, so curious and so methodical, that I suspect he had moments in his last days of lucid, detached scientific curiosity. I’ll bet he grilled his doctors with levels of understanding never expected from a patient without a medical background.

Ricardo Franassovici (Absolute Sounds, Wilson Audio Specialties UK importer), Ken Kessler, and David Wilson in Ken’s listening room in 2000

Ricardo Franassovici (Absolute Sounds, Wilson Audio Specialties UK importer), Ken Kessler, and David Wilson in Ken’s listening room in 2000

Dave’s travails reminded me of a possibly apocryphal tale of another equally disciplined and logical hi-fi giant, the late Alastair Robertson-Aikman of SME. It was rumoured that when he had to have a hip replacement, he specified the construction of the substitute ball-joint. I just loved the idea of AR-A, as he was known, walking around with that famous SME logo in a subdermal location.

Which got me to thinking: I wish the two had met. They represented similar values, in terms of engineering and execution and attention-to-detail, but from differing generations. The two were so alike in so many ways that my imagined fantasy collaboration between them surely would have yielded something magical. This train of thought then led me to musing about the ages of high-end audio, and wondering whether or not we’re on the cusp of a new era, stuck in a rut, or merely at the tail-end of the whole shebang.

As history requires compartmentalisation for clarity’s sake, periods are recognised in decades, centuries, or spans that are determined by events rather than the calendar: the Swinging Sixties, the Roaring Twenties, the Renaissance, the Reformation, the Iron Age. It applies, too, to hi-fi’s history.

What we call high-end audio arbitrarily began in the years after WWII, with what we might define as music reproduction systems in the home consisting of separates that represent more than the mass market offers. In the conflict’s wake were ample supplies of military surplus which enabled engineers who learned their craft while serving in the armed forces to set up civilian businesses. I recall Stan Kelly telling me about his work on radar; a decade later, he created the world’s finest ribbon tweeter.

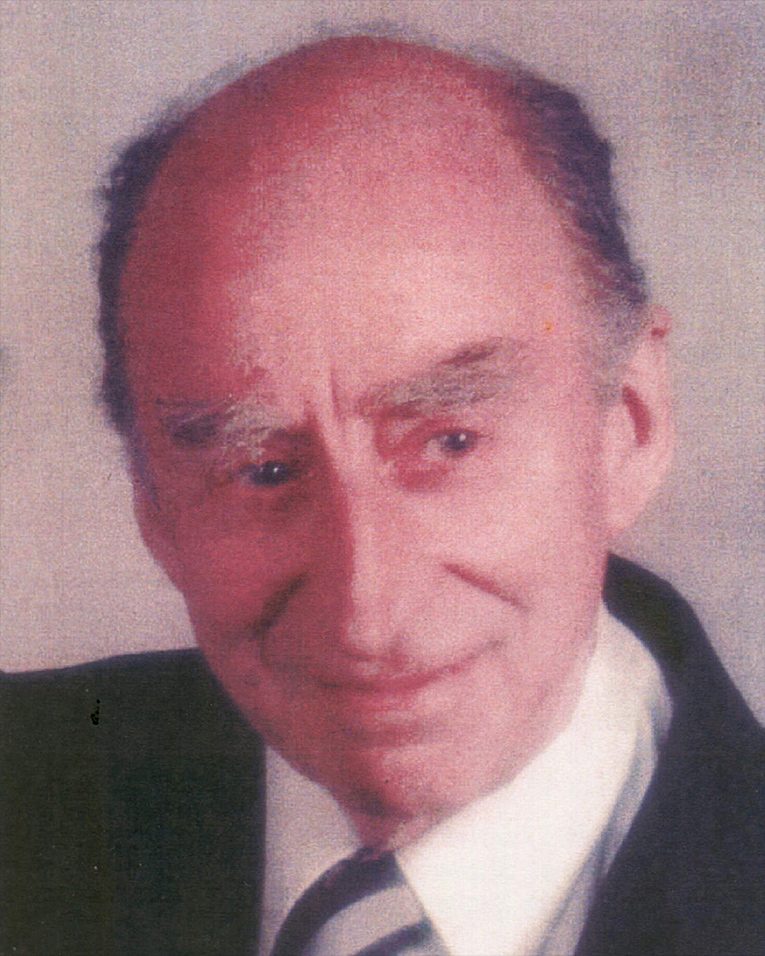

Stan Kelly

Stan Kelly

But back to Dave and A-RA. In my Pisces-with-Virgo-ascending mind, only a tad less anally retentive than one diagnosed with genuine OCD, I define hi-fi in three eras. The first is the Golden Age, when Avery Fisher, David Hafler, Frank McIntosh, Saul Marantz, Paul Klipsch, Edgar Villchur, Henry Kloss, Joe Grado, H.H. Scott, and numerous of their contemporaries did to record players and consoles what the PC did to the typewriter.

Across the pond, Peter Walker of Quad; the above-mentioned Stan Kelly; and Messrs. Leak, Lowther, Voigt, Radford, and others were performing in a similar manner while extant, legacy firms including Tannoy, Wharfedale, and Garrard segued from professional or otherwise-less-lofty market profiles to serve British music enthusiasts. Germany, Switzerland, Japan, Denmark, France, and other countries contributed, too, with names like Ortofon, ReVox, Denon, Sennheiser, and Thorens playing their parts in this new industry.

Peter Walker

Peter Walker

These brands reigned supreme -- even after mass-market Japanese equipment stole the entry-to-mid-level market in the 1960s -- until the end of that decade, on the cusp of the 1970s. All proceeded swimmingly for the founders of the hi-fi separates industry for two-and-a-bit decades, until the perfect storm we’ll call the Second Golden Age, though many would decry it as such.

Mark Levinson remains the poster child for this era, arriving in 1972 with outrageously priced equipment promising better sound -- blasphemy to the ears of those who lived by measurements. Mark was a perfect touchstone for the arrival of subjectivity in the press, through Stereophile’s J. Gordon Holt and The Absolute Sound’s Harry Pearson, who then enabled the likes of Morris Kessler (SAE), Arnie Nudell (Infinity), Harold Beveridge, and too many others to list to push the envelope.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic, what became known as “Flat Earthers” in Great Britain effectively set up what we could now call an anti-free-trade bulwark against US imports -- and make no mistake: then, as now, US brands own the high-end. Linn, Nytech, Rega, Naim, and other brands -- the equivalent of the politically correct in hi-fi terms -- worked in cahoots with the gullible hi-fi press and a network of susceptible retailers to champion British goods over anything imported.

David and Sheryl Lee Wilson meet Paul Klipsch

David and Sheryl Lee Wilson meet Paul Klipsch

Having suffered through that era, I’d prefer not to revisit it -- the lies, the bullying, the deception. It’s old news, an early manifestation of fake news decades before the Internet. And just as people have now realised that nearly all punk music was fundamentally crap (Buzzcocks vs. Led Zeppelin? Sex Pistols vs. the Rolling Stones? Give me a fucking break.), so has the true high-end survived and remained dominated by US brands. Suffice it to say, the same era, despite all of its nasty politics, also gave us Krell, Apogee, MartinLogan, SOTA and -- yes -- Wilson Audio.

Which brings us to the current era, which to me is the equivalent of either the Dark Ages or even the Ice Age. By the early 1990s, post-CD and with home cinema and custom installation proving to be costly distractions, a number of brands fell by the wayside. Thanks to the iPod, mobile phones, streaming, and gaming, consumers shifted their acquisitive desires to items other than serious hi-fi. The high end became an irrelevance for all but the dedicated listeners who didn’t succumb to the lure of convenience over sound quality.

Wilson Audio is one of the survivors, as is SME. Krell is enjoying renewed enthusiasm, the vinyl revival continues to astonish us, and new makes have appeared on a regular basis, among them D’Agostino, TechDAS, EAT, Constellation, and a host of others for whom the market is as voracious as it was 30 years ago.

Dave Wilson left his company in the hands of dedicated staff, and that rarity among rarities: a son, Daryl Wilson, who has created speakers worthy of his father, who taught him better than merely well. Listening to the Yvettes, designed by Daryl, Dave left me with something nobody who knows me would ever believe: optimism.

. . . Ken Kessler

kenk@soundstagenetwork.com