When you’re past 30 -- or so it should be -- a bruised ego should be no more of a concern than a splinter, a slow episode of a favourite TV show, or being put on hold by some call centre where English is not the main language: a minor irritant. You’re not some 14-year-old worried about being cool. But I suppose it depends on one’s levels of insecurity, and I consider myself neither mortally hypersensitive nor brazenly immune to slurs.

When you’re past 30 -- or so it should be -- a bruised ego should be no more of a concern than a splinter, a slow episode of a favourite TV show, or being put on hold by some call centre where English is not the main language: a minor irritant. You’re not some 14-year-old worried about being cool. But I suppose it depends on one’s levels of insecurity, and I consider myself neither mortally hypersensitive nor brazenly immune to slurs.

Still, when one’s professional credibility is at stake, one might take any affront personally, even from a total stranger of limited observational skills. Being accused by a reader I’ve never met of not taking music “seriously” . . . seriously pissed me off.

Most of you are completely unaware that hi-fi journalism was my third field of endeavour, after seven years writing about cars; that followed the very first piece of writing that I ever published, which was an LP review in the late, lamented British magazine, Let It Rock. That was in 1974. I had just turned 22, still at college, and I was blown away, as my dream was to be a rock journalist. Yeah, I know that’s weird: not a rock musician, but a rock critic.

Why that route to a music-related career? For one, I couldn’t play a note. I also wasn’t a songwriter, but I was obsessed with music. How to make it an occupation? By the time I’d reached my sophomore year in college, I had worked in both record and hi-fi stores and realised that I despised selling, thinking that the biggest pile of sell-out/cop-out/cowardice was that “the customer is always right.”

Still, I wanted to be paid to listen to music all day, and it hadn’t occurred to me to aspire to being a hi-fi writer. Forty-three years later, I am still reviewing music, but for Hi-Fi News rather than the rock press, and it’s still what I’d rather do than just about anything else.

In those four decades, I have amassed a gigantic record and CD library that will cause my son, who has no interest in it, much aggravation when he chooses to get rid of it: the necessary dumpster will cost him a couple of grand. And the massive library of music reference books? Another dumpster: I measured it at over 50' of shelf space for the rock history books and triple that for the rock magazines. Too bad the value is zip.

Anyway, I find myself still buying dead-tree books. More telling of my reading habits, though, is that I rarely read fiction anymore -- and I was a voracious consumer of hardboiled detective novels, high fantasy, and SF by the likes of Philip K. Dick and Philip José Farmer. Instead, I now read biographies, including four in a row that, by sheer coincidence, turned out to be related to each other: they just happened to be the top four volumes on my to-read stack.

This column isn’t about book reviews, nor should it be autobiographical. But three of the titles meant more to me than I expected, while the fourth -- the biography of Morris Levy of Roulette Records -- I read out of morbid fascination. And I had completely forgotten that his label was sold to the company that linked the other three: Rhino Records.

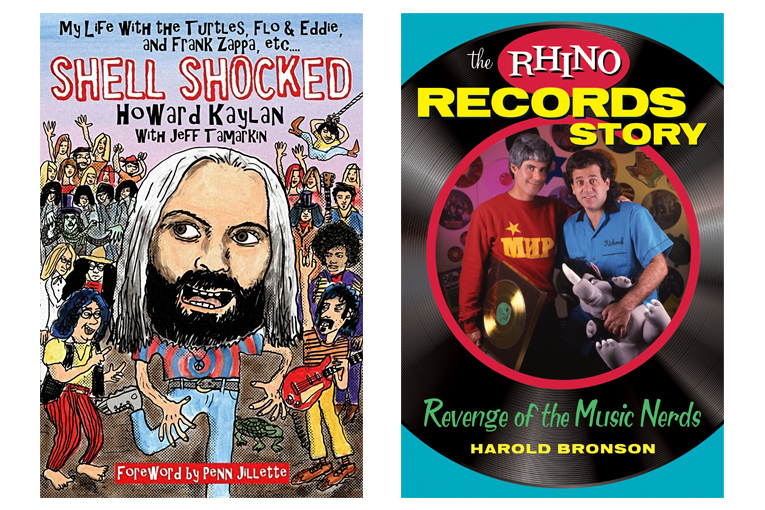

First, I read Howard Kaylan’s Shell Shocked, the autobiography of the Turtles singer and one half of Flo & Eddie. As the Turtles were one of my all-time favourite bands (probably one of the reasons I was said not to be serious about music, which says more about a lack of imagination in my critic), I read the book voraciously: Kaylan met everyone from Jimi Hendrix and the Beatles to Zappa, and all the drug use hadn’t affected his memory. Co-written with ace rock scribe Jeff Tamarkin, it’s one of the most enjoyable rock biographies I’ve ever read. You will laugh out loud.

As for the Rhino connection, that label -- founded by Harold Bronson and Richard Foos -- had the brains, taste, and courage to re-release the Turtles’ entire catalogue when the band was still filed in the “uncool” category -- at least by those who hadn’t bothered to discover their genius despite the Zappa connection. A salient point is that Rhino started out as a hip record store before evolving into one of the very best non-audiophile reissue labels on earth, the others being Sundazed, Ace, Repertoire, Bear Family, and Raven.

Bronson, it turns out, is pretty much the same age as me, and -- like a zillion Baby Boomers -- was hit hard and irretrievably by the arrival of the Beatles and the ensuing British Invasion. His recollections of his musical evolution were like reading a goodly chunk of my own life story. If you loved High Fidelity, ever worked in any form of music or hi-fi retail, or are simply a music-lovin’ audiophile, Bronson’s two volumes will transport you to the pre-CD era, when rock giants walked the earth.

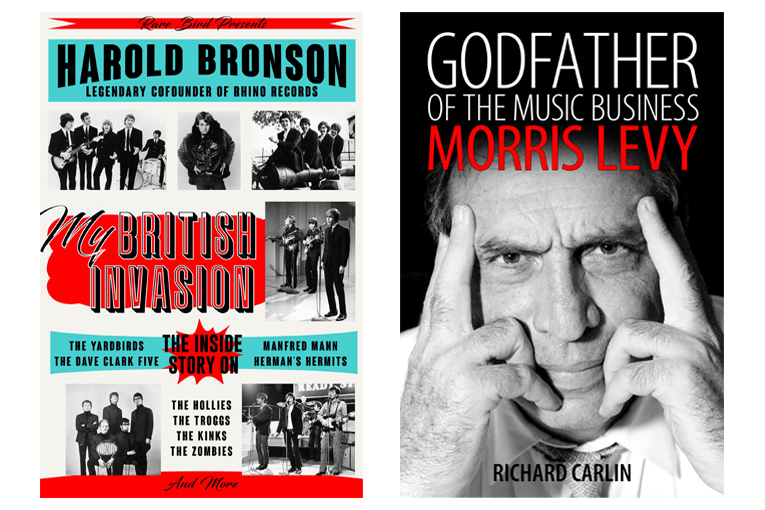

The Rhino Records Story and My British Invasion are complementary but can be read separately. The first tells the story of the store and the label, while the second is more Bronson’s personal history and his appreciation of the rock bands that formed the most important era in rock. Those were the bands that followed the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and the Who, perhaps not as commercially huge but undoubtedly as influential: the Kinks, the Yardbirds (who paved the way for Led Zeppelin), and the ones too many disrespect, but who made incredible pop records. They kicked the US rock scene up the tush, too, inspiring the Byrds, firing up the Beach Boys, and a whole lot more. You will leave this with a different take on the Hollies, the Dave Clark Five, the Troggs, and Herman’s Hermits.

As for Godfather of the Music Business, it’s more about post-war jazz and the birth of rock ’n’ roll than the post-Beatles era, but it segues into the Rhino saga in its final chapter. Up to that point, you learn about the music business’s underbelly, the involvement of gangsters, payola, government investigations, and the practices of one of the most unethical bastards the industry ever suffered. It deserves to be filmed, because the drama is Godfather-esque.

Final thoughts, circle of life and all that, and why two of the books touched me so deeply in my dotage: Harold Bronson and I landed in the UK in the very same week in September 1972. He went back to LA, while I fell in love and stayed. (Yes, I’m still married to the same English rose.) I never met the guy, but I have a few hundred Rhino titles in my collection. And I’m reviewing them still.

. . . Ken Kessler

kenk@soundstagenetwork.com