One of the more divisive issues among audio enthusiasts has long been whether or not high-end, high-priced audio cables can make a significant difference in the sound of a system. Those who advocate for these products tend to believe that cables represent an integral part of their system, and depending on the application, can significantly improve the sound. These folks have no complaints about spending big bucks on such products. Others believe that wire is wire, electrons are electrons, and that interconnects and speaker cables should cost little more than the metals they’re made from. My experience has told me that both arguments have merit, and that determining the result generally depends on weighing two criteria: determining if the engineering behind a given product is legitimate, and evaluating the sound.

One of the more divisive issues among audio enthusiasts has long been whether or not high-end, high-priced audio cables can make a significant difference in the sound of a system. Those who advocate for these products tend to believe that cables represent an integral part of their system, and depending on the application, can significantly improve the sound. These folks have no complaints about spending big bucks on such products. Others believe that wire is wire, electrons are electrons, and that interconnects and speaker cables should cost little more than the metals they’re made from. My experience has told me that both arguments have merit, and that determining the result generally depends on weighing two criteria: determining if the engineering behind a given product is legitimate, and evaluating the sound.

Built from science

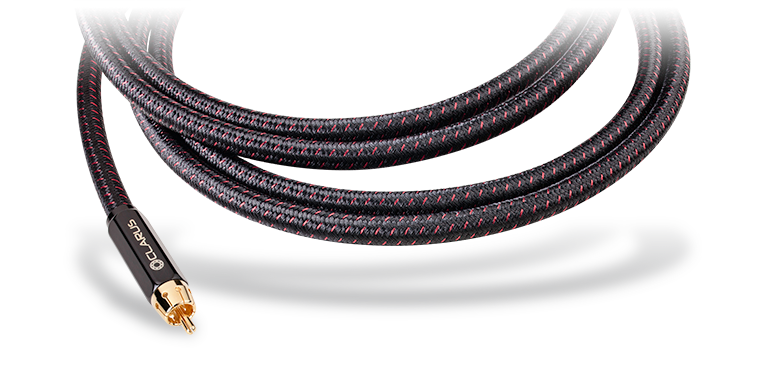

Established in 2011 in Orlando, Florida, Clarus is a subsidiary of Gordon J. Gow Technologies Inc., and sister company to Tributaries Cables. Unlike Tributaries cables, which are well respected in the A/V sector, Clarus cables were created to be used in high-end, two-channel audio systems. While at the 2014 Consumer Electronics Show, I met with Joe Perfito, president and CEO of both companies, and we discussed the two lines of Clarus cables currently available: Aqua and Crimson. Perfito said that both lines are based on the same patented design principles, but differ in that the Crimsons have heavier-gauge wires, slightly different winding topologies, and more expensive connectors. He also told me that “all Clarus products are developed from scratch using no off-the-shelf parts” from their Tributaries brethren, and that every cable in the Clarus family incorporates a host of recently patented or patent-pending technologies that have taken as long as eight years to finalize. What most struck me is Clarus’s statement that these cables are “constructed from the ground up using the finest metallurgy and materials available today.” In such a technologically diverse industry, that’s a pretty bold statement, and I was curious to learn more. Perfito put me in touch with Jay Victor, who designs and engineers all Clarus cables.

At the heart of every Clarus product other than their digital coax and USB cables are three unique conductors, each made from oxygen-free Pure Copper by Ohno Continuous Casting (PCOCC) -- which is, I’m told, the world’s purest copper. Victor believes that this single-crystal, impurity-free construction -- it has only one crystal boundary for every 700’ of cable -- makes PCOCC the ideal metal for use in superior-quality audio cables, as there is a direct correlation between the number of crystal boundaries in a conductor and the purity of signal that conductor can yield. Basically, the fewer crystal boundaries there are, the lower the resistance will be, which in turn decreases distortion and signal loss. Most other manufacturers that use copper as their main conductor tend to use oxygen-free copper (OFC), which has about 400 crystal boundaries per foot. On rare occasions a manufacturer will use linear-crystal oxygen-free copper (LC-OFC), which is essentially the same as OFC but is drawn differently, and has about 70 crystal boundaries per foot. As good as OFC and LC-OFC are, neither approaches the performance potential of PCOCC, according to Clarus.

After choosing the conductor material, Victor focused on addressing flux density and skin effect. Flux density, aka current density, is important to consider when designing an audio cable because the thicker conductors used for lower frequencies are said to have a higher density of magnetic flux concentrated at their cores. Because of this, higher frequencies are forced to the surface of these conductors in another phenomenon, called the skin effect. Depending on the gauge of the conductor, the skin effect will occur to varying degrees, possibly yielding different amounts of high-frequency, bass, and midrange information. After countless hours of listening tests with different gauges and shapes of wires, Victor concluded that midrange frequencies sound better when conducted by flatter, medium-gauge wires, because a flat conductor’s relatively thin cross section lacks the skin depth necessary to support low bass, and the large surface area in contact with the surrounding dielectric material, or insulation, yields high enough capacitance to inhibit high frequencies.

With the conductor shapes and materials for low and midrange frequencies established, Victor’s next challenge was to deal with the highs. He knew that, to do this properly, he would have to design a conductor of low capacitance and low resistance that would also have maximal surface area. The obvious solution would have been a cylindrical conductor with a hollow center, but since these can’t be bent without deformation, this approach wasn’t viable. Victor ended up resurrecting and re-engineering an older technology called tinsel wire. Originally developed for use in the telecommunications industry, tinsel wire consists of one or more thin strips of copper foil wrapped around a nonconductive core. This produced the combination of low capacitance, low resistance, and maximal surface area Victor was looking for, but lacked the robustness required for high-quality audio applications. In adapting the tinsel approach to his needs, Victor ultimately developed the Spiral Ribbon Conductor: thin, spiral-wrapped foil strips of high-grade OFC copper wrapped around a core of polyethylene (PE) strands. To prevent strand interaction, he extruded thin layers of PE insulation over the individual conductors and over the entire assembly.

Victor’s last task was to balance the low, mid, and high frequencies of each of his analog cable models. In doing so, he also experimented with the topology of these cables, particularly the speaker cables, and discovered that twisting the positive and negative conductors together increased phase distortion and thus degraded the audio signal. Making the conductors run parallel seemed to correct this problem, and resulted in all Clarus speaker cables having a rectangular rather than round shape.

When he’d completed the Clarus Crimson speaker cable ($4080 USD per 8’ pair) and analog interconnects ($2000/6’ pair), Victor moved on to develop standard and high-current (HC) AC power cords. Aside from using larger conductors, both the standard ($600/6’) and high-current ($1500/6’) cords differ from other Crimson analog cables in having a proprietary winding technique that involves twisting each cable strand and the completed loom in opposite directions, to maximize noise rejection. The loom is later covered in two layers of shielding, nylon and copper, that provides further noise egress and suppression of leakage while allowing a small amount of internal movement, for greater flexibility.

With the speaker cables (2x10AWG), interconnects (16AWG), and power cables (12AWG and 8AWG respectively) under his belt, Victor began developing a subwoofer cable (16AWG). This cable ($625/6’) was designed with the same approach of triple-type, individually insulated conductors as its analog brethren, but was optimized to its application.

The Crimson digital coax cable ($450/6’) is a bit of a departure from the rest of the Crimson family in being the first to make use of silver. The precious metal later found its way into the Crimson USB cable, but is used in the coax to plate an 18AWG conductor core of solid PCOCC that is then sheathed in a skin/foam/skin dielectric, which in turn is wrapped in a dual-layer, silver-plated shield of OFC copper that permits greater flexibility, and provides excellent levels of noise suppression -- much like the dual-layer shielding used in the power cords. At each end of the Crimson digital coax are innovative terminators that have been angled on the inside of the pressure teeth so that, when connected, they fit flat on the receiving conductor. The AES/EBU digital cable ($850/6') is a three-conductor cable similar in design to the coax, but using solid PCOCC copper and terminated with Neutrik XLR connectors.

The most recent Crimson model is the USB cable ($350/6’), which is unique in that, unlike most of its competition, it uses larger-than-normal (22AWG) signal conductors of solid, silver-plated PCOCC, and separate OFC power conductors (20AWG). Larger power conductors are used simply to maximize current delivery and extend the possible cable length, but the signal conductors are a whole different story. Similar to those found in the Crimson analog cables, these conductors differ in being round, smaller in gauge, and coated in solid silver. When I asked Jay Victor why silver was used here, he said, “Digital USB signals travel primarily on the surface (skin) of the conductors. Since silver is a better conductor than copper, and the conductor itself is solid, the signal can be transferred with less loss and jitter.” To maintain signal purity in a conductor laid side by side with a power conductor, each conductor is isolated with layers of double-sided AL foil shields over PE dielectrics. The two double-shielded conductors are then brought together within a final layer of silver-plated braid, but not before being cloaked in yet another layer of double-sided foil shielding.

The power cables are made in China. All other Crimson cables are handmade on-site in Orlando, and terminated with proprietary, CNC-machined, gold-plated connectors also made in-house (except for the balanced cables, which have Neutrik terminations).

Performance

I should have observed Clarus’s recommended 72-hour break-in period before doing any listening, but having the curiosity of a kid in a candy store, I sat down right away to get a taste of what I was in for. I was immediately struck by a decidedly forward midrange, and wondered if it would remain after break-in. I pulled myself out of my listening chair, set the Simaudio MiND streamer to Random, and let the system play for about a week.

When I returned, I cued up the first track I’d listened to after installing the Clarus Crimsons: “Border Reiver,” from Mark Knopfler’s Get Lucky (CD, Vertigo 02527 08674), and paid particular attention to his voice.

Within minutes, I realized that the question was no longer whether I would like Clarus’s Crimson line of cables, but by how much they would exceed my expectations. The midrange dominance I’d heard at first had almost completely disappeared; what little remained of it seemed only to present a clearer, more crisply delineated image of well-balanced sound. After listening to “Border Reiver” several times, I began to hear other subtle changes -- such as the repositioning of Michael McGoldrick’s flute in the song’s opening seconds. Not only was the flute now farther back on the stage, it had a vividness of sound that I’d never heard with my Cardas and Kimber cables. The dimensionality conveyed by Phil Cunningham’s accordion opened up this track in ways I hadn’t heard before, and Richard Bennett’s guitar strumming sounded livelier, particularly in dynamic passages. However, this newfound overtness came at a price, especially when Cunningham’s accordion was at full tilt -- the more I relished the vividness of all things north of about 2kHz, the less I could appreciate Glenn Worf’s bass.

To more easily dissect what I was hearing, I moved on to some less densely recorded music. “Nothing Yet,” from Tracy Chapman’s Telling Stories (CD, Elektra 62478), told me a story alright, exemplifying the degrees of separation between Chapman’s voice, the percussion instruments, and the bass. This time, there was no tipping of the scales one way or the other -- all three elements now sounded perfectly balanced. The electric guitar at the beginning of the track sounded euphoric, filling the room with lingering notes. Chapman’s voice quickly followed suit, positioning her at center stage with a controlled sense of scale, tightly focused imaging, and an abundance of textural detail -- I could easily hear the breath beneath her voice. As the first verse ends, the kick drum seemed to come out of nowhere like a kick in the pants. The beat of the drum was so well conveyed that I began to revel in its assertiveness as I anticipated each beat. Other percussion transients were handled expertly on both sides of the soundstage, helping to place each instrument accurately, with convincing timing. I listened to this track many times at various volume levels, and could find no fault with how the Crimsons were communicating anything.

I heard much of the same while listening to various high-resolution recordings, such as “Desert Rose,” from Sting’s Brand New Day (24-bit/48kHz FLAC, A&M); and “Come as You Are,” from Nirvana’s Nevermind (24/96 FLAC, Geffen/HDtracks). The ear-opening levels of resolution of both tracks let me hear deep into the recordings and appreciate spatial cues that often go unremarked, such as the airiness of the brass in “Come as You Are,” and the depth of the background vocals in “Desert Rose.” Track after track, the Crimsons seemed to convey simply what was on the recording, no more and no less, and I reveled in it all -- especially when listening to something as simple as David Gilmour’s acoustic guitar in the opening seconds of the title track of Pink Floyd’s Wish You Were Here (24/88.2 FLAC, Columbia/Legacy/Analogue Productions). Of course, such utter transparency can be a problem. When a recording was of poor quality, the Crimsons let me know in a hurry. But with very good recordings, these cables showcased every iota of dynamism, depth, and resolution they contained. Thankfully, most recordings let the Crimsons’ “no more and no less” sound seem just about right almost all of the time.

I found this level of honesty refreshing. While paying attention to newfound nuances ranging from bass-laden dynamic swings to subtle, holograph-like passages, I appreciated more and more the time that Jay Victor had spent tinkering with and voicing the Crimsons. Their balance of bottom-end authority and an articulate, airy, and dimensional top end was quite convincing on its own -- and combined with the ever-so-slightly forward midrange, the sound was downright compelling. After listening for hours to various types of recordings, and having begun to realize that finding a stumbling block for the Crimson loom might take a very long time, I decided to compare them directly with my reference cables.

Each time I had the Clarus Crimsons in my system, I hoped that I would acclimate to them enough that, when I removed them, any sonic differences between them and my reference loom would be more obvious. I was indeed able to hear a few subtle differences, but even after weeks of listening to countless tracks through both looms, I can’t say that those differences led me to conclude that the Crimsons were any better or worse than my Kimber and Cardas cables -- just different. Overall, they projected comparable levels of dynamics, dimensionality, image focus, and neutrality, though the Claruses consistently had the upper hand in terms of transparency and retrieval of detail. It was a draw in the bottom end as well -- both sets of cables sounded exceedingly resolving, articulate, and propulsive.

The two looms began to differentiate themselves when listening at very high volumes. The Clarus cables retained their iron-fisted bass, midrange punch, and top-end detail, but at times I found their sheer honesty too much of a good thing. In “Desert Rose,” for example, Sting’s voice began to sound a touch brittle, and grew disproportionately enough in scale to become noticeably dominant. With my Kimber-Cardas loom I heard no such traits -- they maintained their somewhat sweeter, smoother, more refined sound regardless of volume.

At most any sane volume level, with “Red Book” or high-resolution recordings, the Clarus cables’ honesty and transparency were sheer delights. Microlevel details were a bit easier to hear, mid- and low-bass notes came across a touch fuller and better articulated, and the midrange, while neutral and lively, never disassociated itself from the overall sound, as it did at much higher volumes.

Conclusion

The Clarus Crimson cables are engineered from science, and Clarus uses nothing but the highest-quality materials and components while adhering to the strictest standards during their construction. At all but the most ridiculously loud volume levels, I found the entire Crimson line to be the closest thing to invisible that I have heard in my system. These cables are expensive, but I have grown to respect them as no-holds-barred, reference-level products that simply tell you how it is. What more can you ask for from a high-quality cable? Highly recommended!

. . . Aron Garrecht

arong@soundstagenetwork.com

Associated Equipment

- Speakers -- Rockport Technologies Atria

- Subwoofers -- JL Audio Fathom f112 (2)

- Amplifier -- Classé CA-M300 (2), Halcro MC50

- Preamplifier -- Classé CP-800, Marantz AV8801

- Sources -- Ayre Acoustics C5xeMP CD player, Oppo BDP-103 universal BD player

- Cables -- Kimber Kable Select KS-6063 speaker cables and Select 1126 interconnects, Cardas Clear Blue Beyond power cables and Clear digital cables

- Power conditioner -- Torus Power AVR2 20A

Clarus Crimson Speaker

Price: $4080 USD/8’ pair.

Clarus Crimson Balanced Interconnect

Price: $2000 USD/2m pair.

Clarus Crimson AES/EBU

Price: $850 USD/2m.

Clarus Crimson Digital Coax

Price: $450 USD/2m.

Clarus Crimson USB

Price: $350 USD/2m.

Clarus Crimson Power (HC)

Price: $1500/6’.

Clarus Crimson Power

Price: $600/6’.

Warranty (all): Lifetime.

Clarus Cable

Gordon J. Gow Technologies, Inc.

6448 Pinecastle Blvd., Suite 101

Orlando, FL 32809

Phone: (888) 554-2514, (888) 554-2494

Fax: (800) 553-1366

E-mail: info@claruscable.com

Website: www.claruscable.com