I’m no early adopter because there’s no upside. Invest too early and you not only end up spending too much money, you might end up with an expensive white elephant as the technology continues to progress -- or, in the worst case, withers on the vine, a victim of market forces. This is why I never took sides in the debate of SACD vs. DVD-Audio, and instead waited for a universal player or music server that would meet my criteria for the ultimate in sound quality and convenience.

I’m no early adopter because there’s no upside. Invest too early and you not only end up spending too much money, you might end up with an expensive white elephant as the technology continues to progress -- or, in the worst case, withers on the vine, a victim of market forces. This is why I never took sides in the debate of SACD vs. DVD-Audio, and instead waited for a universal player or music server that would meet my criteria for the ultimate in sound quality and convenience.

I had no intention of making my digital source an Apple iPod, but the idea of using Apple’s iTunes with a computer as the server first entered my mind around 2004, a few years after the iPod’s launch. Unfortunately, at that time the only way I knew of getting the music out of my iMac and into a stereo system was by using Apple’s AirTunes, which didn’t seem to be the most sonically sound (sorry) method of connecting source to system.

Things began to look promising with the launch of the Slim Devices Squeezebox and, in 2006, the Slim Devices Transporter. The Transporter received great reviews in several publications, including the SoundStage! Network's SoundStage! A/V, so in 2008 I took the plunge with the Transporter ($1900 USD).

My initial impression of the Transporter was that while it organized my expansive CD collection and improved the convenience of listening to music via Wi-Fi streaming, sonically it wasn’t much, if at all, better than my Wadia 830 CD player, which I’d bought in 2000. On top of that, I never cottoned to the Squeezebox Server software that organized the music, nor its cheap remote, with its many buttons and rounded bottom -- the latter caused it to topple over at the slightest touch. (I’ve since replaced that remote with a free Squeezebox app for my iPhone 4S.) Because of this lack of a wholesale improvement in sound quality, the Wadia 830 remained my primary digital source for another two years.

In fall 2010, things took a significant turn for the better. It was then that I added Sonic Studio’s Amarra playback software and directly connected my iMac to the Transporter with the Halide Design USB-to-S/PDIF Bridge via the Transporter’s BNC digital input. The improvement in the Transporter’s performance via direct connection vs. Wi-Fi streaming was so great -- and was so much better than using the Halide Bridge connected to the BNC input of my Wadia -- that I stopped using the Wadia. The Transporter became my sole digital source.

But I knew that even the Logitech Transporter was just a way station. The upper limit of its playback resolution was limited to 24-bit/96kHz, and with the increasing availability of higher-resolution downloads, I itched to find something better. Additionally, via the Halide Bridge, the Transporter was prone to interruptions in data flow -- I experienced a lot of dropouts. Therefore, over the past year I’ve been eagerly scouring audiophile publications and the Internet for news about the latest and greatest digital-to-analog converters -- and when Meitner Audio announced the $7000 USD MA-1 in 2011, I took notice.

Design and philosophy

Ed Meitner has a well-deserved reputation for audio excellence. He first came to prominence in the pro-audio field, with the creation of a recording-studio console in which the commonly used mechanical sliders, which are susceptible to variations related to environmental factors, were replaced with far more stable electronic gain cells. Eventually, working with various companies, he branched out into the production of other electronics, including guitar amps and consumer preamps and amplifiers, all the while aiming to provide the highest-quality sound reproduction at lower prices. With the launch of the competing high-resolution audio formats SACD and DVD-Audio, Meitner founded EMM Labs to design and build D/A converters for DSD-based recording studios. The success of these DACs among audio professionals led audiophiles to seek them out for home use; eventually, EMM Labs shifted away from pro and into consumer audio.

When I first read about the MA-1, a few things about its design appealed to me. The MA-1 is just a DAC, plain and simple. Unlike many of the competing DACs available today, the MA-1 does not attempt to be a Swiss Army Knife component. There are no user-selectable filters, no preamp or power-amp or headphone-amp functions, and, above all, no analog or digital volume control. Instead of filling up the MA-1 with features and the sonic compromises and cost of adding them, Meitner chose to focus the MA-1 solely on converting digital audio signals to analog.

While derived from EMM Labs’ more expensive professional- and audiophile-grade DACs, Meitner Audio’s products were designed from the outset to offer comparable audio quality at far lower prices. While the MA-1 is by no means inexpensive at a list price of $7000, that sum compares favorably to those of competing DACs of similar quality, and is considerably less expensive than EMM Labs’ own offerings.

The MA-1 supports all popular sample rates -- 44.1, 48, 88.2, 96, 176.4, and 192kHz -- and a software upgrade will support the 1-bit/2.8224MHz resolution of Direct Stream Digital (DSD), the format used to record the high-resolution tracks of SACDs. In addition to legacy digital inputs, the MA-1 features an asynchronous USB 2.0 input. Regardless of the input used, the MA-1 is truly plug’n’play, with very little setup required.

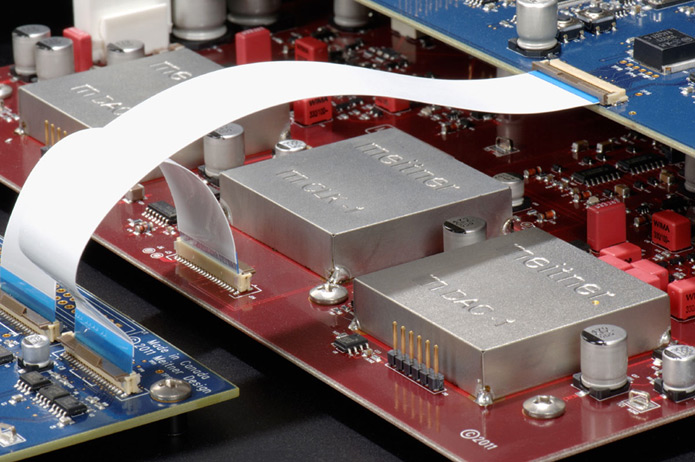

No off-the-shelf product, the MA-1 is packed with proprietary technologies and their corresponding Meitner-related acronyms. All six inputs features Meitner’s Meitner Frequency Acquisition System (MFAST) asynchronous technology, which acquires the digital signal, buffers it, then strips out the jitter. After that, the signal is fed to the MA-1’s Meitner Digital Audio Translator (MDAT). MDAT upsamples both DSD and PCM signals to 5.6MHz -- twice the standard SACD sampling rate -- preparing them for digital-to-analog conversion using the 5.6MHz MDAC modules.

The DAC itself has three modules. Two are the MDACs, discreet, dual-differential, digital-to-analog conversion circuits; the other is the MCLK, a high-purity master clock.

The MA-1 looks quietly elegant, with an uncluttered front panel of 1/4”-thick machined aluminum that’s purposeful, logically laid out, and available in silver or black; both look great. On the left side are a standby/power-save button and the Meitner logo, the latter etched in relief; on the right is the model number. Between these, from right to left, are the six Input Select buttons: AES/EBU, Coax 1 and 2, Tos 1 and 2, and USB Audio. Above and below the inputs are two rows of corresponding blue LEDs, six in each row. The upper LEDs indicate the input selected, the lower ones the sample frequency of the file being played. Supplied with the MA-1 is a small, sleek remote control of black plastic, with which you can change the input.

At the upper left of the rear panel are the digital inputs, in the same order as the input buttons on the front. In the lower-left and center sections are the analog line outputs, one set balanced and one set single-ended. In the center, above the outputs, are an RS-232 communication port, and a USB port for updating the MA-1’s software. At the right are the main power switch and the IEC receptacle for the detachable power cord.

The rest of the MA-1 is clad in black steel and aluminum. It measures 17”W x 3.6”H x 15.6”D and weighs a reasonable 16.4 pounds.

Setup

After removing the MA-1 from its carton, I placed it on my rack, plugged it into my power conditioner, connected it to my iMac with a 4m-long Cardas Audio Clear USB cable, and powered it up. There was a hiccup.

For some reason, the iMac’s Audio MIDI window wouldn’t recognize the MA-1, and whatever music I played was overlaid with static, pops, and clicks. A quick call to Meitner’s support staff confirmed that the MA-1 was capable of driving up to 5m lengths of USB cable with no problem; they suspected that there was something wrong with either the USB cable or my iMac. I also had a MacBook on hand, so I connected the Cardas Clear to the MacBook’s USB port and, lo and behold, music poured forth. Clearly, there was a problem with my iMac. On a hunch, I tried a 1m-long USB cable from my wife’s printer -- not only did my iMac recognize the MA-1, but there were none of the sonic problems I’d heard earlier. I exchanged my 4m Cardas Clear for a 1m length of the same, and the iMac had no further problems talking to the MA-1. However, that meant that my iMac was on the floor next to my equipment rack and was unavailable for any other use.

Like all Meitner products, the MA-1 had been burned in continuously for one week before shipping, and it was recommended that I continue breaking it in for another two weeks before doing any serious listening. Although I took that advice, playing the break-in track from the Cardas/Ayre Acoustics Irrational, But Efficacious! burn-in CD, I felt that whatever break-in Meitner had done at the factory must have been sufficient, as the MA-1 sounded just fine straight out of the box -- I noted no great change in character between first setting it up and after two weeks of break-in.

Sound

Throughout my listening, I used a combination of 16- and 24-bit recordings with sample rates ranging from 44.1 to 192kHz, beginning with “Red Book” 16/44.1 AIFF recordings and progressing to files of higher resolution.

Right away, I could tell that the MA-1 was something special. Music flowed effortlessly from the “blackest” of backgrounds, with an ease and liquidity that was consistent with the analog ideal. I haven’t had vinyl playback in any of my systems since 1988, and being a naturally inclined digiphile, I really didn’t miss the pops and crackles. Whenever audiophiles would negatively comment on my lack of a turntable, I would think, They’re the same as tube fanatics -- in love with a particular sound at the expense of resolution and dynamic range. If that’s what they prefer, more power to them, but it’s not what I’m looking for.

However, the MA-1 smoothed out the sound, though not at the expense of detail and resolution -- music had an effortless quality that sounded so much more open and natural than what I’d experienced with any other digital player. I’m not about to go out and buy a turntable and a load of LPs, but now I can see what I’ve been missing all these years. Even the most cacophonous recordings were engaging and fatigue-free.

One of the best cinematic and musical experiences I’ve had in the last year was watching The Secret of Kells with my six-year-old daughter. I didn’t see the film during its theatrical release in 2009, so I was excited to see that it was available for instant streaming on Netflix. Not only is it a magical movie with a great story and otherworldly animation, but its soundtrack music, composed and arranged by Bruno Coulais, is a beautiful mixture of Norse, Celtic, and monastic choral music that simultaneously sounds ancient and modern. The original soundtrack recording, Brendan and the Secret of Kells (16/44.1 AIFF, Indie Europe/Zoom), is unavailable in the US, so I shelled out big bucks on Amazon.com to buy an import edition. I haven’t once regretted that purchase. (Because everyone’s taste in music is different, I hesitate to recommend that someone else buy a particular recording -- but if you love world music and want an audiophile spectacular that can really show off what your system is capable of resolving, you might want to consider this disc, which is dynamically rich and gorgeously recorded.)

The MA-1 conveyed Coulais’s music in spectacular fashion. The title track begins with a combination of woodwinds, strings, chimes, and bass drum, and sounds ethereal and ghostly. The bass drum and woodwinds begin it and continue to anchor the piece, overlaid by a solitary flute and chimes in the background. Later, a plucked mandolin adds melodic counterpoint, and the bass drum’s low frequencies add solidity and weight. Through the MA-1, not only were the individual instruments and the music as a whole more cleanly defined, I was able to hear more deeply into the music -- wealths of microdetails and subtle sonic cues were disclosed that had not been apparent in previous hearings. All of this combined to not only relay a more lifelike sound, but also to convey this hauntingly beautiful music’s spooky majesty. Awesome stuff.

Keith Jarrett has long been a favorite artist of mine, and listening to his Sun Bear Concerts (16/44.1 AIFF, ECM) via the MA-1 was a real highlight. Despite having been taped 36 years ago, and some minimal hiss aside, these recordings hold up very well against more modern ones. These solo-piano performances showed off the MA-1’s best -- not only were the notes that Jarrett actually played cleanly and clearly rendered, but all sorts of subtle harmonics in the piano’s sound were more audible. Even the instrument’s action and pedals were audible to an extent I’d not heard before. Additionally, the soundstages were broad and deep, with exceptional reproductions of the five venues in Japan in which these concerts were recorded. It all added up to a level of realism that was present not only in the sweet spot of my listening room -- when I stood outside the room with the volume turned up to realistic levels, it sounded as if Jarrett were performing live.

One band that’s recently spent a lot of time on my playlist has been the power trio Tia Carrera (you know, from Wayne’s World . . . not!). Imagine the bastard child of Black Sabbath and Soundgarden, with a smattering of Gov’t Mule, and minus the voices, and you get the idea. This droning jam band is one of my favorite recent rock discoveries, but while well recorded, their albums, like most rock records, are not audiophile-grade. Via the MA-1, the almost industrial-sounding soundscapes of Cosmic Priestess (16/44.1 AIFF, Small Stone) were laid bare in all their dense, crunchy glory -- I was able to turn the volume way up for extended, fatigue-free listening.

The Meitner’s 16/44.1 “Red Book” bona fides established, I eagerly investigated its high-resolution capabilities.

In my previous experience of hi-rez disc players, the improvements I heard with hi-rez discs were audible, just not jaw-droppingly so. I had to admit to being a bit disappointed, given all the hype about SACD and DVD-A. The manufacturer of one of those players cautioned me that hi-rez recordings were more about expanding the soundstage and exhibiting a more lifelike presentation than about the ultimate in from-the-groove resolution. And with that player, that’s just what I heard. However, after borrowing a friend’s Oppo Digital BDP-83SE universal Blu-ray player, I heard improvements beyond those. I realized that there was more to be heard.

Regardless of the sample rate, with the MA-1 I heard great improvements in sound quality, resolution, and timing with 24-bit over 16-bit recordings. And while I did hear improvements in soundstaging, the most obvious difference was that the music in 24-bit recordings actually sounded slower than their 16-bit counterparts -- not as if I’d switched from 45 to 33.33rpm, but with a more relaxed quality that resulted in a smoother, more realistic, less mechanical sound.

Listening to In Session, by Albert King and Stevie Ray Vaughn (24/96 AIFF, Stax/HDtracks), it was so much easier to hear the heavy-gauge strings Vaughn favored for his Stratocaster. The tone was much deeper and warmer, and the strings had much more bite via the MA-1. When Vaughn reached for the high notes, his Strat really sang. Although King and Vaughn’s between-tracks banter was flat, the music itself was fully fleshed out and three-dimensional, revealing the distinct interplay between these two friends and mutual admirers.

Because the Logitech Transporter’s upper limit of resolution is 24-bit/96kHz, I had no 24/176.4 or 24/192 files on hand -- but having the MA-1 in my system was an incentive to buy some. I’m very familiar with Bill Evans’s classic album Waltz for Debby, recorded at the Village Vanguard in New York City in June 1961. I’m also familiar with the acoustic signature of that storied club, having attended many shows there. Until recently, my copy of that album was the JVC XRCD edition, which was a marked sonic improvement over the OJC CD version, but the stereo imaging was still largely tied to the speaker positions, with little center fill. With my newest version (24/192 AIFF, Riverside/HDtracks), Evans’s playing was more emotionally intense because of the improvements in rhythm and timing that this higher-rez recording provided. Having sat in the Village Vanguard for many performances, I had to grin each time I heard the rumble of the subway, which was much more noticeable in the 24/192 than in my XRCD version. There was also better center fill, with much less hard-left/hard-right imaging. Even more important, the club’s acoustic was conveyed just as I remembered it, and brought back memories of all the performances I’d experienced in that legendary room. How much of this improvement was due to the recording and how much to the MA-1 was not something I could account for, since I’d never before had a DAC capable of playing this high a resolution.

Comparison

At more than three times the price, I expected the MA-1 ($7000) to sound better than my Logitech Transporter ($1900), with or without the Halide Design Bridge ($450). What I was not expecting was how thoroughly the Transporter was outclassed.

Regardless of the recording’s resolution, the Transporter sounded consistently edgier, particularly in the treble, which sounded almost spotlit. With rock recordings, I found I could listen for much longer periods at louder volumes via the MA-1 without fatigue -- even to highly compressed recordings. With recordings of acoustic jazz or classical, the MA-1 had a smoother top end and significantly more air, with improvements in top-octave resolution. Bass, too, was considerably tighter and distinct via the MA-1; through the Transporter, bass sounded distinctly flabbier and less well formed.

The Transporter’s soundstage was more constricted, particularly in depth, and suffered in comparison with regard to focus and 3D imaging -- the MA-1 presented the more natural and realistic sonic pictures.

How does the Meitner it stack up to some real competition? In the middle of last year, I had a dCS Debussy DAC ($$11,500) in my system for a week. While I can’t make any sweeping judgments, from the notes I took at that time, it seems that the MA-1 could play at the Debussy’s level.

Conclusions

In every parameter, the Meitner MA-1 so far exceeded my expectations that it brought home to me how big an improvement could be wrought in digital recordings. Yes, I expected that 24-bit recordings would sound better than 16-bit, and they did -- but what really impressed me was how much better my 16-bit recordings could sound, and how much I’ve been missing from them all these years. Face it: Most of our digital recordings are 16-bit, and the catalog of higher-resolution music files available for download is still limited. Anything that will improve the lion’s share of our libraries is most welcome.

When a SoundStage! Hi-Fi reviewer evaluates an exceptional component, it receives the accolade of Reviewers’ Choice. I love the Meitner MA-1 so much that I’m putting my money down and making it my choice for my new digital reference.

. . . Uday Reddy

udayr@soundstagenetwork.com

Associated Equipment

- Loudspeakers -- Wilson Audio Sophia

- Integrated amplifier -- Jeff Rowland Design Group Concentra

- Digital sources -- Slim Devices/Logitech Transporter music server, Devilsound USB DAC, Apple iMac OS 10.7.3 with iTunes 10.5.3 and Amarra 2.3.3

- Interconnects -- Cardas Audio Neutral Reference, Halide Design S/PDIF asynchronous USB Bridge with BNC termination

- Speaker cables -- Cardas Audio Neutral Reference

- Accessories -- Audio Power Industries Power Pack II power conditioner; Cardas Twinlink and Cardas Cross power cords; Cardas Audio Signature XLR, RCA, and BNC caps; Cardas/Ayre Acoustics Irrational, But Efficacious! burn-in CD

Meitner Audio MA-1 Digital-to-Analog Converter

Price: $7000 USD.

Warranty: Three years parts and labor.

Meitner Audio

119-5065 13th Street SE

Calgary, Alberta T2G 5M8

Canada

Phone: (403) 225-4161

Fax: (403) 225-2330

Website: www.meitner.com