Stereo preamplifiers are usually pretty straightforward components to write about, but JE Audio’s VL10.1 tubed model is an exception. It’s not because it has a lot of features, or uses technology that’s difficult to describe, or is priced too high -- it retails for $5000 USD, which, for the reasons stated below, I consider a bargain. The VL10.1 is difficult to write about because of its combination of a very high level of performance and three operational quirks.

Stereo preamplifiers are usually pretty straightforward components to write about, but JE Audio’s VL10.1 tubed model is an exception. It’s not because it has a lot of features, or uses technology that’s difficult to describe, or is priced too high -- it retails for $5000 USD, which, for the reasons stated below, I consider a bargain. The VL10.1 is difficult to write about because of its combination of a very high level of performance and three operational quirks.

The challenge is in writing a review that’s wildly positive in most ways while also being somewhat cautionary. The VL10.1 will be an incredible preamplifier for some listeners, but not all. Also, when I’m very enthusiastic about the performance of a product, as I am about this one, I like to know as much as possible about its manufacturer before I give it my wholehearted endorsement. But I don’t know much about JE Audio, and, based in Hong Kong, they’re too far away for me to learn much more. The best I can do is focus on what the VL10.1 actually does.

Description

JE Audio’s VL10.1 is a stout, extremely well-built component that measures 17.5”W x 6”H x 15.5”D and weighs 31 pounds. The brushed-aluminum panels that form most of the case are about .25” thick. The large, cylindrical metal legs -- posts might be a better word for them -- that form each corner end in feet of soft plastic, so that the VL10.1 will rest gently on a shelf.

The input selector, volume knob, and power button are also of metal, and feel sturdy. The RCA and XLR connectors on the rear panel seem of very good quality, and the way they peek out through cleanly cut holes in the thick aluminum rear panel is a nice, refined touch. All told, the VL10.1 is very well built and its finish work is superb, including the metal grille on the top surface, which lets you see the tubes glowing in their recess while, at the same time, protecting them. The power-on phase is gentle: First, the VL10.1 mutes itself for about 30 seconds, until the circuit settles.

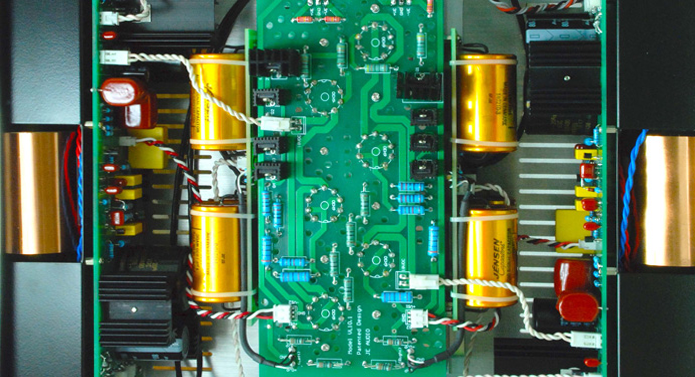

The VL10.1 uses three 6H30 dual-triode tubes per channel, configured in what JEA calls a Wideband Unity Balanced Amplifier (WUBA) design, which they’ve patented. According to their literature, “The WUBA is a single-gain-stage wideband balanced differential amplifier design that contains no load resistors, no buffers and no followers. Because of employing just one single gain stage, the WUBA will have the lowest phase shift compared with conventional multi-stage feedback amplifiers.” The tubes are said to have an ultimate life of 10,000 hours, but after about 5000 hours they should be tested for possible replacement. JEA calculates a tube life of three to four years, assuming the VL10.1 is used an average of four hours a day. MOSFET devices are used as a current source, and no global negative feedback is used, something JEA feels contributes to a more realistic, natural sound.

On the subject of tubes, this is a good place to mention the first of those three operational quirks. Whether because of the tube type used, or the use of tubes in the first place, I found the VL10.1 to be fairly microphonic -- that is, it amplified mechanical noise. If I tapped the case or a tube, or even switched the input selector, I heard a slight ringing through my speakers. Granted, it wasn’t that big a deal -- when you’re playing music, you’re not supposed to be tapping your preamp with your fingers or with anything else. I mention it because 1) solid-state preamps aren’t nearly as microphonic as tube amps, and 2) even among tubed preamps, the VL10.1 was more microphonic than most.

That input selector, volume control, and power button are the only controls available -- there’s not even a remote control. The VL10.1 is designed for the purist who wants simple preamp operation rather than a full-featured control center. But the rear panel boasts enough inputs to connect a sufficient number of sources -- three pairs of single-ended on RCA, and three pairs balanced on XLR -- as well as a pair of recording outputs (balanced), two pairs of outputs (one single-ended, one balanced) to connect to a power amp, and an IEC-compatible power-cord inlet. I tried every one of the single-ended and balanced ins and outs, and the VL10.1 worked fine regardless of the configuration. But the VL10.1 is claimed to be a fully balanced design; John Lam, owner and chief designer at JE Audio, says that it performs its best via its balanced ins and outs, which is how I did the bulk of my listening.

Given that JEA is based in Hong Kong, I asked about service. “In the regions that we have dealers, the products will be serviced by them,” Lam told me. “In the regions that we don’t have dealers, the customers have to send back the product to us for service. The customer pays the inbound freight charge, while the factory pays the outbound freight charge.” To my way of thinking, that sounds more than fair.

Sound

Some people, even reviewers, take a long time to determine whether or not a component sounds good, something they often attribute to break-in or some other phenomenon. Perhaps with some components that’s true, or perhaps they’re just getting used to the sound. It took me only moments to know that the sound of the VL10.1 was not only different from that of other preamps I’ve listened to, it also just might be downright spectacular. More important, those first impressions not only held up, they were strengthened and reaffirmed over six months of using the VL10.1 in a variety of system configurations.

The VL10.1’s rich, robust character made music sound harmonically “alive” -- musical performances were strikingly present. Voices, in particular, sounded shockingly real, with spooky you-are-there presence. One of my favorite recordings is Blue Rodeo’s Five Days in July (CD, Discovery 77013), which has a live sound that’s inherent in the recording, and has sounded good through almost every decent system I’ve tried it with. The two lead singers, Jim Cuddy and Greg Keelor, are very well recorded. When I played this disc on a combo of Simaudio Moon Evolution 650D transport-DAC, the VL10.1, a Bryston 4B SST2 amplifier, and my reference Revel Ultima Salon2 speakers, with Siltech cables throughout, it didn’t sound just decent or good, but downright incredible. Five Days in July sounded richer, more immediate, and more detailed than I’d ever heard before, and Cuddy’s and Keelor’s voices hung in space, tangible and as close to real as I’ve heard them. Those impressions held up when I swapped in the Blue Circle Audio BC204 and Simaudio Moon 400M amps, which told me that it wasn’t only the Bryston that the VL10.1 sounded great with. It also meant that the JEA worked beautifully with solid-state designs (the Bryston and Simaudio are pure solid-state; the hybrid Blue Circle has a tubed input stage and a solid-state output stage). To those who wonder how the VL10.1 might partner with a pure-tube amplifier, I can say only “I don’t know.” I have no tube amps here right now.

Voices weren’t the only things the VL10.1 rendered incredibly well. The JEA’s bass was very deep, quite tight, and well rounded -- i.e., impactful, but with a slight bit of bloom. This meant that the kick drum in “5 Days in May,” the opening track of Five Days in July, had a touch more richness and presence in the bass than I’m used to hearing from, say, typical solid-state preamps, which are generally iron-fisted and tight in that region. Instead, the VL10.1 exuded a presence that was very different from a closed-in, thin, and dry sound.

Drums are dominant in the opening of “Grim Travellers,” from Bruce Cockburn’s Humans: Deluxe Edition (CD, True North TND 317); through the VL10.1, they had a wonderful mix of warmth, weight, and punch that made this music sound rhythmic and majestic. But if there was a flaw in the VL10.1’s sound, it was that it lacked that hard-driving wallop that’s inherent in the sound of iron-fisted solid-state preamps. Some people might like something a little less present and alive, and prefer that tighter, more closed-in sound. I found that this richness and presence sounded startlingly real, and more like the sound of drums in live performances.

The VL10.1’s highs, too, differed from what I’m used to -- extended and clean, for sure, but with a bell-like richness in the top octaves that gave a little meat to cymbal crashes and the very top end of a guitar. In short, the richness and presence in the VL10.1’s sound didn’t live only in the midrange, but extended down through the bass and up through the highs. I don’t often use the term lively to describe audio components, but it certainly applies to this one.

I wasn’t all that surprised by the VL10.1’s presence and richness -- tubes are known for that, which is why so many audiophiles like them. By comparison, almost all solid-state devices sound thin. But if that were all the VL10.1 had going for it, I’d classify its performance as good but not great -- after all, you can find lots of tubed preamps that will give you that kind of sound. But the VL10.1 delivered much more.

What I wasn’t expecting to hear from the VL10.1 was what completely blew me away: those “spectacular” qualities I alluded to earlier. The VL10.1 had a startlingly open, immediate, and transparent sound on a par with the very best preamps I’ve heard, regardless of price. It gave a clear view into the recording, it sounded as spacious as anything, and it had the ability to reveal an astonishing amount of detail in a recording. Why did this surprise me? Tube-based designs can obviously sound rich, but that doesn’t mean they’ll also sound transparent and detailed. The fact that many of them don’t is why many audiophiles prefer high-resolution solid-state designs, even if, by comparison, the latter tend to sound thin. But again, the VL10.1 was an exception to the rule. What was perplexing about its sound was that it unraveled such copious detail despite another of its characteristics, the second quirk I wanted to point out.

Tube preamps are never dead-quiet. Some listeners find their noise off-putting, particularly if they’re used to putting an ear close to a speaker’s midrange driver or tweeter and hearing the dead silence of good solid-state amplification. The VL10.1 is fairly noisy -- in fact, it’s noisier than other tube preamps I’ve heard. That noise is still within the “acceptable” range -- it wasn’t so loud as to interfere with even quiet music -- but it was definitely there, and it wasn’t affected by the volume control. When the JEA was turned on without music playing, there was always a steady “tube rush” through the speakers that was audible from a foot or two away, depending on the general noise level in the room: Shhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh. In my listening chair, eight to ten feet away, I didn’t hear a thing, and you won’t either (unless you live in the world’s quietest room and can hear like a bat).

Given all that, what the VL10.1 did was revelatory, and a hair short of miraculous. It passed along a wealth of musical detail above the surface of the noise that completely immersed the room in a wall-to-wall soundstage of mind-blowing depth and amazing image specificity. This was astonishing. After hearing so much hiss, the last thing I expected was to also hear reference-level detail and astounding imaging and soundstaging. After all, to hear every nuance in a recording, and to reproduce such soundstaging, don’t you need dead-quiet electronics? Apparently not. Color me impressed.

And color me curious about how this was happening. I couldn’t explain the phenomenon, so I talked with a number of people about it, and two of them, though they hadn’t heard the VL10.1, came up with some interesting theories. One was Paul Miller, editor of the UK’s Hi-Fi News. He thought that the near-constant level of noise I described might be acting as “dither” -- essentially, randomized noise, often used in digital audio and digital imaging to create smoother, less objectionable aural and visual images. Dither can also increase the perception of resolution. A color-limited dithered image, for example, can look as if it has much more color in it. This argument was bolstered by the fact that I was able to more easily focus on music with the VL10.1, and often astonished by the level of detail I heard; and that I could listen for hours on end without ever approaching listening fatigue. In fact, the VL10.1 was the most detailed preamp I’d ever heard and the most listenable -- two traits that don’t always go hand in hand. So . . . perhaps.

Our own S. Andrea Sundaram wondered if I could hear such immediacy, transparency, and detail because of the apparent simplicity of the VL10.1’s circuit design, which could result in less screwing-up of the audio signal, which in turn could overshadow things like low-level noise, which is anyway masked by higher-level music signals. Indeed, I’ve noticed that many “simpler” designs sound decidedly superior to their more complex counterparts because they sound more immediate and alive. Many designers go with the “less is more” philosophy for precisely these reasons. Again: perhaps.

Perhaps it was a combination of these two theories, or something else entirely -- JE Audio might point to their WUBA circuit topology -- but does it really matter? Regardless of the cause, the effect was that the VL10.1’s immediacy, transparency, and detail floored me. Add to those the rich musical textures the JE conveyed, and its golden highs and deep, rounded bass, and the sum total of the VL10.1’s sonic characteristics made it one of the very best-sounding preamps I’ve heard -- and all for $5000, which might qualify it as a steal. These days, preamps can cost quite a bit more than that, and many of those that do don’t sound better than the VL10.1.

But I must temper such enthusiastic praise with caution and mention the VL10.1’s third and final quirk. I discovered it during one of my marathon listening sessions: a problem that designer John Lam explained and, it appears, addressed in my review sample. Tubes run quite hot; according to Lam, as the VL10.1’s tubes warm up to their stable operating temperature, their glass casings expand slightly, and can make a little noise that is amplified by the electrical circuit and heard through the speakers as a subtle ting. It sounds like a tiny bead, one just a bit bigger than a grain of sand, dropped onto a cymbal. You’d be hard-pressed to hear this ting while music is playing (although a couple of times I did), but, according to Lam, it should disappear completely within 30 minutes of startup, as soon as the tubes reach their stable operating temperature.

With the review sample’s original set of tubes I could hear an occasional ting when no music was playing, even hours after I’d switched on the VL10.1. John Lam, who always responded almost immediately to my e-mails, sent me a brand-new set of fully tested tubes. After 15 or so minutes of warm-up, they made no sound whatsoever, other than the “tube rush” I’ve talked about. Given the fact that JE Audio easily fixed this problem might be reason enough for me not to mention it; but given my high praise of the VL10.1’s sound and the probability that readers will seek out and buy this preamp, I wanted everything about my time with it to be known.

Conclusions

I love how the JE Audio VL10.1 preamplifier sounds in my system. It’s one of the few products in recent memory that has thrilled me -- partly because of its great build quality, but mostly because of its incredible sound, which is quite unlike that of any other preamp I’ve heard. When it comes to the pleasure of listening to music, right now I’ll choose the VL10.1 over anything else. And, as a value-oriented guy, I like the asking price.

But the VL10.1 is not for everyone. It’s not rich in features -- there’s not even a remote control -- and the three small quirks I describe above might give some pause. Then there’s something I haven’t mentioned that’s inherent to any tube-based design: Unlike solid-state devices, tubes regularly wear out and need to be replaced. Audiophiles who want to listen to music free of such inconvenience might want to steer clear of the VL10.1 -- but then, those audiophiles wouldn’t want any tubed product.

But if you don’t mind the greater level of maintenance that tubes demand and don’t need a lot of features, then you must hear the VL10.1 before you spend $5000, or more, on anything else. The JE Audio VL10.1 sounds shockingly good. If it pushes your sonic pleasure buttons as firmly as it did mine, you may have found one of the very best-sounding preamplifiers you can buy. To my ears, the VL10.1 is a reference-class preamplifier at a real-world price.

. . . Doug Schneider

das@soundstagenetwork.com

Associated Equipment

- Speakers -- Revel Ultima Salon2

- Amplifiers -- Blue Circle Audio BC204, Bryston 4B SST2, Simaudio Moon 400M

- Preamplifiers -- Lamm Audio LL2.1 Deluxe, Simaudio Moon 350P

- Digital sources -- Simaudio Moon Evolution 650D DAC-transport, Zandèn Audio Systems 2500S CD player, Sony Vaio laptop, Ayre Acoustics QB-9 USB DAC, Hegel HD10 DAC

- Speaker cables -- Crystal Cable Piccolo, DH Labs Silver Sonic Q-10 Signature, Nirvana S-L, Nordost Valkyrja, Siltech Classic Anniversary 330L

- Interconnects -- Crystal Cable Piccolo, Nirvana S-L, Nordost Quattro Fil, Siltech Classic Anniversary 330i

JE Audio VL10.1 Preamplifier

Price: $5000 USD.

Warranty: Three years parts and labor; 90 days for tubes.

Jonce Technology Ltd.

Room 1618-1620, Park-In Commercial Center

56 Dundas Street, Monkok

Kowloon, Hong Kong

Phone: (852) 3527 0966

Website: www.je-audio.com

JE Audio responds:

Thank you very much for Doug Schneider’s thorough and excellent review of the VL10.1 preamp. Doug has pointed out the strengths of the VL10.1 preamp in great detail. The strengths of the VL10.1 are, in fact, a result of the 6H30 vacuum tube and the patented, fully balanced preamp circuit, which makes the 6H30 sing at its best. However, it should be noted that the 6H30 has a little more microphonic effect than commonly used audio tubes such as the 12AX7, 12AU7, 6DJ8, and 6SN7, etc.

The 6H30 tube was originally designed for high-frequency pulse amplifiers for RADAR applications in the former Soviet Union, and was never intended for use in audio amplification. Since the 6H30 has a frame grid construction to achieve high transconductance, there will be some microphonics. But if care had been taken in constructing the 6H30's grid and filament, as it is in other commonly used audio tubes, the microphonic effect could have been greatly reduced. Now, when we choose the 6H30 for preamp application, we have to accept that fact. However, unless one taps the chassis of the preamp, one does not hear it in normal operation.

There is some slight rush of current noise that can be heard from the tweeter of the loudspeaker. This is, in fact, a result of biasing the 6H30 in high current and not using global negative feedback. If global negative feedback is employed, it can greatly reduce the rush of current noise. But the price paid for this will be very high, as it affects audio performance. Nevertheless, the user will not hear the rush of current noise more than 2’ away from the loudspeaker, even if a loudspeaker with 90dB sensitivity is used.

John Lam

JE Audio