![[SoundStage!]](../sslogo3.gif) The Vinyl Word The Vinyl WordBack Issue Article |

||||||||||||||||

December 2007 Artemis Labs PH-1 Phono Stage

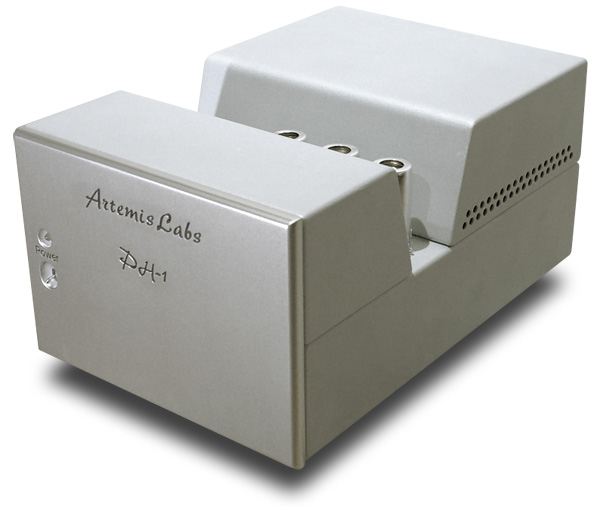

Ah, the listening season -- that time of year here in the Upper Midwest when the glow of tubes turns the music room all toasty, and cats doze by the amps to the sounds of Mozart, Mendelssohn and Mahler. Like cognac for my cochleae on these chilly evenings, music played from records warms my home. It’s been 50 years since RCA began releasing vinyl under their Living Stereo banner, but in yet another holiday season the market for records and the equipment needed to play them remains strong, and a steady stream of new and updated products continues the march of innovation for this high-resolution medium. Standing, as we are, on the precipice of the digital-audio-server age, nothing testifies to a belief in the viability of vinyl playback like a new company offering a phono stage as one of its first products. Artemis Labs was started by Sean Ta with the goal of delivering vacuum-tube-based high-end components built in the USA using time-tested techniques and the latest in high-quality parts. The company released a phono stage and preamp in 2003, and Artemis products have been gaining in prominence ever since. Like many high-end manufacturers that started small, Artemis Labs does the building itself with custom-made components. As Sean relayed to me: "The chassis and front panel are built by our neighbor. It takes about a day to put a preamp together and one more to test and burn-in. Everything is done by hand at our location. We manufacture the board that we hand wire point-to-point, and we are starting to wind our own transformer. We try to keep everything in house as much as we can." The Artemis Labs PH-1 ($3500 USD) is a nicely compact phono stage longer than it is wide. It measures 8-1/2"W x 6 1/2"H x 14 3/4"D and weighs in at a chunky 24 pounds. . The fit and finish of its all-metal chassis bespeak sturdy quality. A polished silver aluminum faceplate sports a power toggle and an indicator LED that changes color according to the progress of the unit’s power-up or shutdown cycle -- red during a 40-second mute period, and green when the PH-1 is ready to play. On its backside, the PH-1 provides one pair of RCA inputs and two pair of RCA outputs. This might seem odd if you believe there are more vinylphiles who own two-'arm turntables than multiple line stages. However, if you are into transcribing your records to a digital format through a sound card or the like, it makes a lot of sense when you want to record and listen at the same time. Also on the back is a ground terminal for your turntable, along with the ubiquitous IEC power-cord connector. Next to the PH-1’s inputs, under a cover held by (maddeningly tiny) thumbscrews, is a 3M TexTool Zero Insertion Force (ZIF) socket. If your cartridge prefers a different load than the default 47k ohms, this clever device offers an easy way to adjust load impedance by adding resistors. A lever opens and shuts three gold-plated slots per channel, into which resistor leads are inserted. With the resistors in place, pull the lever and the slots clamp down on the leads like louvered window blinds. Use the same ZIF socket to add capacitance for moving-magnet cartridges.

The PH-1’s tube-based all-triode circuitry was designed for Artemis Labs by John Atwood of One Electron. Atwood has done chip and logic design for Intel, taught college-level classes in amplifier construction, and for several years was the technical editor of Vacuum Tube Valley magazine. The PH-1 embodies what Atwood calls his "third-generation phono preamp design," and he describes it as "smoother and liquid" relative to earlier work. Amplification comes from three gain stages and via active devices only; no step-up transformers are used. The initial input stage amplifies the cartridge’s microvolt signal through a Russian 6N1P dual-triode tube, which takes a fixed-bias supplied by two 1.5-volt type N alkaline batteries. The bias batteries live under the backside cover next to the ZIF socket. Because the bias draws virtually no current, the batteries should last until their expiration dates. The unit’s passive RIAA equalization follows this first gain stage. Artemis specs say it goes out beyond 40kHz. The second gain stage uses one dual-triode 12AX7 per channel, and each channel uses one triode from its tube’s pair. Each of the triodes in a tube has its own heater, which allows running it independently of the other. The design cleverly uses triode #1 of the right channel’s 12AX7 and triode #2 of its left channel 12AX7. The unused triode in each channel’s tube effectively becomes a spare. When the tubes wear-out, simply swap their socket positions and start consuming the previously unused portion of the tube. Because one half of each tube is idle, both run cooler. Artemis trademarks this feature as "Cool Swap." The third gain stage uses two 5687 dual-triodes and likewise employs Cool Swap. It’s worth noting the 5687 is no longer in production, though the manual claims large NOS quantities remain available. The final two gain stages use about 5dB negative feedback. The specs claim the PH-1 has an output impedance of approximately 1300 ohms at 1kHz. The unit inverts phase; therefore, if your preamp and amplifier do not, you’ll want to switch the plus and minus leads of your phono cartridge or swap the connectors of your speaker cables at their binding posts. While there are no standards, manufacturers of fixed-gain phono-stages without step-up trannies typically find the gain sweet spot for moving-coils in the 57dB to 64dB range. Artemis Labs takes a different approach, splitting the market between low-output moving-coil cartridges (0.7mV or lower) and high-to-medium output MM or MC cartridges (0.7mV or higher). Along with the PH-1 and its 50dB of gain, Artemis Labs offers the PL-1, a high-output phono stage with gain fixed at 70dB. It’s basically a PH-1 with internal step-up transformers. The manufacturer chose the PH-1 as best suited to my cartridge. The PH-1’s manual is one of the most thorough and well-laid-out pieces of audio-equipment documentation I’ve come across. To see a schematic and read more about the PH-1's technical details, download a copy at the Artemis Labs website. Review context and use My analog front-end includes a Teres 320 turntable sporting an SME V tonearm and a Transfiguration Orpheus moving-coil cartridge. Cartridge output is approximately 0.68mV. To spin the turntable’s 37-pound cocobolo platter, I alternated between the Teres Reference II motor with Mylar tape and the new Verus rim-drive motor and controller. Silver Audio’s Silver Breeze tonearm cable connected the Orpheus to an Audio Research PH7 phono stage or directly to the balanced inputs of an Atma-Sphere MP-1 Mk III full-function preamp. The single-ended PH7 fed into the tape monitor inputs of the MP-1. An Ayre C-5xe universal player handled SACD and Red Book duties (though no silver discs were spun for this review.) The MP-1 Mk III preamplifier drove Atma-Sphere MA-1 Mk. III mono amplifiers, which powered Audio Physic Avanti Century speakers. A Conrad-Johnson ACT2 line-stage preamp also did duty during the evaluation period. Cables and power cords came from Shunyata Research. The speakers were connected to the amps via Orion Helix speaker cables, while Antares Helix and Altair interconnects tied together the various electronics. Everything plugged into a state-of-the-art Shunyata Hydra V-Ray power conditioner; power cords for the electronics were either Python Helix Alpha or Taipan, while the V-Ray received wall current through an Anaconda Helix Alpha. It was into this system a demonstrator PH-1 arrived already broken-in with tubes installed. I connected it to a single-ended tape monitor input of the MP-1 and used that preamp’s polarity switch to adjust for the PH-1’s inverted phase. Adding resistors to configure the phono stage for cartridge load was simple with the ZIF socket. The Atma-Sphere MP-1 Mk III revealed the sonic character of load resistors from different manufacturers. After auditioning a variety of makes and resistance values, I settled on using it with 150-ohm Audio Note Tantalums. Similar trials with the PH-1 demonstrated that it was not particularly discriminating of such differences. I ended up using 200-Ohm nude Vishays in the PH-1, and the Transfiguration cartridge seemed satisfied. The PH-1 operated flawlessly during its time in my system. It emitted no hum, seemed unaffected by RFI or proximity to other electronics, and caused no pops or clicks during power cycling. Music through the PH-1 sounded best after a 30-minute warm-up. Listening to music with the PH-1 I think it was Harry Pearson who long ago mused about the correlation between the color of a component and the character of its sound. Silver sparkled cool and gold glowed warm -- yada, yada. With its lambent silver frontispiece and frosty flanks, the Artemis Labs PH-1 belied that notion. Working backward from sound to color, I wrote "sorrel butter crème" when I first listened. I can’t explain the odd mixture, but those were the words written in my listening notes when I played "Wouldn’t It Be Nice" by the Beach Boys from the 1999 stereo mix of their Pet Sounds album [Capitol Records 7243 5 21241 1 4]. The near-angelic voices of Brian Wilson and Mike Love brought a smile of reminiscence. I heard a sound that was warm but not lush, with smooth, multi-layered harmonies, and I wondered why more bands didn’t have accordion players. Even with all the reverb, the PH-1 and the Transfiguration Orpheus gave hints of how Wilson stitched the tune together on the studio’s mixing board. It all played out entirely behind my nearfield speakers, as the soundstage assumed an isosceles trapezoidal shape, narrower in front and wider in the rear, stretching beyond the speakers’ side boundaries. Voices presented slightly recessed into the center, and instruments had nice separation as the soundstage tapered outward. One hallmark of a competent phono stage is a refusal to abdicate the tiny voltage fluctuations handed to it by a cartridge. No amount of downstream electronic goodness can rehabilitate a missing signal. The Transfiguration Orpheus worked hard to pull musical subtlety from the grooves, and here the PH-1 did not disappoint. A consistent representation of small detail proved to be one of its strengths. From the refined grace of Sviatoslav Richter’s phrasing in Beethoven’s first Sonata for Piano and Cello in F major [Philips 835 182/83AY] to the internal kibitzing among fluttering woodwinds in Sibelius’s magnificent Second Symphony (Barbirolli and the Royal Philharmonic [Chesky CR3]), the PH-1 demonstrated deft handling of microdynamic detail. I heard the rosiny pull of Rostropovich’s bow on his cello and the small noises from musicians as they shifted about while performing. These sounds did not draw attention to themselves; rather, they appeared as details available for the hearing when one focused on them, serving as sonic cues to the reality of people making music in time. Nearly rivaling Dorati’s on Mercury, Ernest Ansermet’s version of Stravinsky’s "Firebird Suite" demands a broad dynamic range from many instruments (L'Orchestre de la Suisse Romande [Speakers Corner/Decca SXL 2017]). Here, the PH-1 demonstrated a smooth, full-bodied sound with a composed cadence and a touch of warmth. It proved itself an adept performer under pressing conditions across the middle frequencies. Violins and trumpets in the mids and highs rose nicely without forwardness or etch. The treble satisfied on fundamentals and harmonics, albeit they were a bit dry at the very top end. Higher-frequency transient attack was a touch softer, and decay was not quite as fulfilled as what I heard in the middle register, where bloom was nicely evident. Timpani, bassoons, and basses exhibited solid low-end weight with tonal definition. On occasion, their leading-edge articulation and dynamic impact was a wee bit rounded, more so during loud complex passages when many instruments played at once. At some points in the score this led to the impression of a relaxed pace, but the performance was never off balance or overly congested. Individual bass lines were confident -- the solo "wolf-hunting" bass pizzicato at the start of the second movement of the Sibelius piece was taut and timbral. It was easy to get a sense of the orchestra’s layout as this musical line passed from bass to cello. For a second opinion from a larger work, I played an RTI test pressing of Stanislaw Skrowaczewski conducting the Minnesota Orchestra in Ravel’s "La Valse" [Analogue Productions TAPC 007]. It was another sonic showpiece, with dynamic swings from balmy to boisterous -- "the apotheosis of the Viennese Waltz," as Ravel described it. The PH-1's soundstage was quite broad, more so toward its rear, as often is the case in live recording venues where percussion and bigger brass sit spread out in the back. There were ambient cues, the PH-1 delivering back and side reflections. In the upper mids, I heard articulate and detailed resolution as it nicely reproduced the breathy flutter and trills from flutes as they cut below the strings. Instruments held firmly to their spaces without growing artificially large or small in proportion to their dynamic intensity. In passages with big dynamic swings -- from piano to fortissimo and back -- the PH-1 never ran out of gas, although definition from lower string sections and lower brass could get a bit homogenized, with slightly less clarity than I heard under less-demanding dynamic conditions. Comparison On hand for comparison with the PH-1 were the phono stage of the Atma-Sphere MP-1 Mk III ($12,100 fully loaded) and the Audio Research PH7 dedicated phono stage ($5995). Both units have received SoundStage! Reviewers’ Choice nods along with other industry accolades. I found that each consistently performed with internal coherency and balance. I don’t know if it is fair to compare the PH-1 to them, but it certainly helps gauge relative merit for your audiophile dollar. Gain from the ARC PH7 is 57.5dB and the MP-1’s phono-stage gain is around 60dB. Listening to the PH-1 at my accustomed loudness meant turning up the line-stage volume control to about 11:00 or so. (An SPL meter confirmed close equivalence in output.) While the MP-1’s line stage is near silent, this additional volume caused increased audible tube rush from the PH-1, to the point where it was obvious during music’s quiet passages. Although I rarely turn up the MP-1’s phono stage that high, at 11:00 tube rush was about the same, but its pitch was distinctly lower, and to my ears that made it easier to ignore. At comparable volume, the PH7 was the quietest of the three tube units and nearly as quiet as some solid-state phono stages, except at very high volume levels. For sonic comparison, I listened to each phono stage with an array of material. With Traffic’s rendition of the English folk song "John Barleycorn" (John Barleycorn Must Die [Island, 900580-1]), the PH-1 sounded open and inviting, with a firm location of instruments and musicians in space. Overall, the sound was quite nice, with a smooth, dulcet midrange. The PH-1 captured the piano and nuanced tambourine playing deep in the background -- details sometimes missed by other units. Lead and backing vocals through the PH-1 were closer together in the center and slightly recessed in perspective, whereas the PH7 rendered Winwood’s lead with more forthrightness and separation from Jim Capaldi's backup. Surface noise seemed to follow the PH-1’s tube noise -- imparted with a slightly higher pitch. By direct comparison, the PH7 was clearer, and the PH-1 exhibited a faint tonal haze, as if a thin film kept the final pixels of timbral color from emerging. Listening to Rostropovich and Richter play the Beethoven Cello Sonata No.1 made it obvious why these phono stages fell into different weight classes. The PH-1 presented the duet as a rather somber affair, restrained and vaguely less chromatic, yet nicely resolved with subtle microdynamic intonation. The playing was marvelous, and even if you didn’t know the musician’s names, their virtuosity was self-evident. And yet, the music I heard sounded as if it came through a lens from another time, an older time -- it left me muttering to myself "Nice first effort, Ludwig, I hope you have a better day tomorrow." Then my ears perked up. Listening to the Cello Sonata through the Atma-Sphere preamp was like hearing the piece for the first time. Rostropovich’s playing took on a clear, emotive sweetness as he roused vigor from the music and harmonic richness from his cello. No longer did I hear this as older music. It unfolded with the purpose and motion of the musicians making it. With rhythm restored, somber was forced from the field. The temporal perspective shifted as the MP-1's phono stage transported me to Vienna 1963. I sensed the air and tension surrounding the instruments within their venue. Richter conjured subtle sonic shades of color from the piano -- his attack forceful with courage and risk, his delicacy intense. Together the artists summoned Beethoven’s genius, and the music sounded as fresh and alive as the day of its making. Playing the tune through the PH7 lost none of this dynamic energy or harmonic completeness; there it gained a blushing of warmth, though sounded a wee bit cooler than with the PH-1. Call it rhythmic aptitude or the absence of temporal smearing, but the PH7 and MP-1 Mk III refused to obscure the musician’s ardor, as each component drew notes from a clearer, deeper harmonic well. Costing, as they do, multiples more than the PH-1, I expected a higher level of refinement, and I was not disappointed. Conclusion They say it don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that midrange, and that’s where the Artemis Labs PH-1 delivered a high degree of musical satisfaction. With its resolved sonic detail, firm, dimensional images and natural ambience, the PH-1 offered a lot to like in a quality, well-priced package. While the PH-1 did not always yield the last word in dynamics and timing compared with much costlier units, it remains a strong contender in its price range. It might be just the ticket for adding the air and richness of tubes to an otherwise solid-state system. Pay attention to the output of the cartridge you use it with and it should reward your ears with its open, warm character. Kudos to Artemis Labs for a strong opening effort and their commitment to vinyl playback in a new century! ...Tim Aucremann

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

![[SoundStage!]](../sslogo3.gif) All Contents All ContentsCopyright © 2007 SoundStage! All Rights Reserved |