![[SoundStage!]](../sslogo3.gif) Paradise with James Saxon Paradise with James SaxonBack Issue Article |

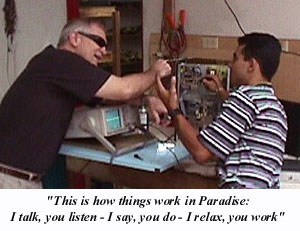

| July 1999 Work Watching As much as the next guy, I like to watch people work. On errands around town, I can’t pass a construction site without gawking. Traffic cops, garbage men, and telephone linesmen are street performers in my eyes. Indoors, I admire doctors, bartenders, and lap dancers. On vacations, I like to watch native craftsmen and artisans ply their trades. Wherever there is work being done, I try to lend an eye. For this reason, a trip to the stereo repair shop is not all drudgery. Were I a mere consumer, service personnel would shoo me from their domain. However, being a member of the audio dealer’s fraternity entitles me to hover around while technical types troubleshoot my dead components. Since I am totally devoid of electronics insight, my countenance resembles that of a loyal dog -- somewhat puzzled, but eagerly attentive. I love to watch a skilled technician poke around

electronic innards, taking measurements, fiddling with oscilloscope dials. Being an

activist type, I occasionally ask helpful questions, such as, "Are you Over the years, I have spent numerous hours in the audio tailler of my friend and associate Roberto Herrera. Although Roberto is a few years younger than I, he has been repairing, selling and listening critically to stereo equipment for over 30 years. In Paradise, Roberto is audiófilo numero uno. He is also a technician par excellence, and suffers my presence stoically. However, at mucho dollars per hour, his time is too valuable to spend on non-essential repair work. Therefore, I have been forced to go from spectator to participant in audio troubleshooting. With Roberto’s guidance, I have learned to check for blown fuses, examine cable connections, and verify source material, including whether the right switch has been flipped, in order to save a trip to the repair shop. It is amazing how many audio problems can be solved without lifting a chassis cover. I dread those occasions when professional help is definitely required. Despite having witnessed plenty of pyrotechnics at Casa Saxon over the years, I still get scared when flame and smoke erupt from a component. Nevertheless, on those sparkling occasions, I now spring into action like a well-drilled infantryman. First, I disconnect the power cord, since flipping the on/off switch of a burning component does not always work. Secondly, I curse the manufacturer to high hell, and thirdly, I hunt surreptitiously for erroneous connections that might have caused a short. As one who has touched speaker cable ends together while running a power amplifier red hot, I am proud to say this stupidity on my part is no longer a regular occurrence. The most catastrophic event is one that occurs for no apparent reason while music is playing. On at least five occasions amplifiers have exploded without outside interference. Such mysterious self-damage often defies Roberto’s efforts to fix them, requiring me to beg the manufacturer for a "return authorization" number. Some of the smaller fabricators are very reluctant to part with an RA. Boxing up and shipping components back is my job, unfortunately, and I dread the bending and lifting required. In the gymnasium I have the benefit of a warm-period. Whoever warms up to lift heavy boxes? As you may know, components weigh less when they arrive than when they have to be returned to the manufacturer. Although in my teens I worked part-time as a pipe-fitter and can still sweat a joint (old plumbers never die -- they just ooze away), I have never learned to solder. When I took up the stereo hobby at age 36, I was office-bound and believed myself inept at manual labor -- with reason. Whenever I tried to fix something, it usually got worse. For years, I hired hands for everything from changing a tire to sharpening knives. This costly procedure at least afforded me the pleasure of watching competence in action. Of special fascination has been the soldering of others. From watching Ernie Viotty of Octave Research repair my OR-1 to peering over Roberto’s shoulder in front of a dead amp of current vintage, I have been fortunate to witness masters of the lead/flux art in action. Their fine skill resembles that of a watchmaker, whose dexterity fills me with awe. Having spent many solemn hours in the company of burnt-component repairmen, it’s a wonder I haven’t learned to solder by osmosis. There is a darker reason I cannot solder. It is called fear of shocks. For some reason, I am willing to stick a fork into a blazing toaster, but petrified to place a hand inside an unplugged component. Maybe at some unconscious level all those resistors remind me of dead maggots. Devoid of interest in probing with fingers or even test instruments, I see no reason why I should plug in and hold a hot soldering iron either. Also, I am sure I will singe myself with ridiculous frequency. Fear of getting shocked is another reason I marvel at technicians’ skills. I admire their bravery. Astoundingly, to this lily-liver, Roberto is expert at fixing tube gear, which, as we all should know, contains lethal voltages even after being unplugged for awhile. One day while proving his courage, Roberto absorbed a jolt from a tube preamplifier, which he tossed across the room. After shaking his wounded hand, he went right back to work. His words, however, were cautionary. "I hate electricity, " he said. My fear of shocks went way up after that. Luckily for me, audio manufacturers have begun to take a modular approach to component design, eliminating the need to de-solder and re-solder in order to effect repairs. My career as a non-soldering audio peddler has thus been prolonged. By creating a way to unplug critical signal-path components and replace them with a push-in circuit board, Madrigal and other manufacturers have made my audio life less fear-inducing and more gratifying. My first experience with plug-and-play modifications was when a customer ordered an upgrade kit for his preamplifier. For some reason, Dr. Equis insisted I do the update personally. This filled me with trepidation until I remembered my final examination in Economics 10. In order to think like an economist, I decided to feel like one and so wore a suit and tie to the exam, which gave me enough confidence to bluff my way through. In order to face the No.38 upgrade, I adopted a similar plan by replacing dress shirt and trousers with T-shirt and jeans. Suddenly, I felt like a two-fisted lab technician (don’t ask me why) and tackled the kit with perfect results the first time out. Since then, I have adopted a positive attitude about upgrade kits and actually look forward to installing them. It gives me satisfaction to hear the improvement in a component’s sound, knowing the final step was in my hands. Recently, I accepted an assignment that was not as user-friendly as I had hoped. New 24/96 circuitry for Z-Systems’ amazing digital tone-control unit, the rdp-1, is said to be field replaceable. And it is -- in hands of one more dexterous. In my stubby mitts, however, the circuit board that was supposed to come loose wouldn’t, and when it did, the new replacement board seemed several inches too large to slide in. Since I am of the "bigger hammer" school of physics, I attempted to pound the board into place with my fist. This drew the attention of Monica the maid, who noticed the bleeding knuckles. She stood beside me with a paper towel while I pushed and pulled on the circuit board, cursed and cajoled, banged and blustered and finally called Z-Systems for help. Mr. Z. himself, Glenn Zelniker, admitted that changing boards only seemed difficult but really wasn’t. As he talked me through the procedure, I followed along in real time, huffing and puffing. Then I realized Monica the maid was doing something I never expected. She was watching me work. I, the voyeur, the inveterate on-looker, was the source of someone else’s wonderment. The dog had suddenly become the master. Failure in front of Monica’s attentive eyes was impossible: I knew I could finish the job. Soaking up the balance of Glenn’s instructions, I discarded the phone like a man on a mission. With a modicum of help from Monica, I completed the job, imperfectly to be sure, but taking the circuit board back out and reversing it took far less effort the second time around. Since then, I have actually invited people over to watch me perform -- no soldering, but everything short of it, from small tweaks to major upgrades. I particularly like the latest development in upgrade wizardry: downloading software from the Internet. On a visit to Madrigal Audio Laboratories several years ago, I was exposed to the future possibilities of such downloads and received brief instruction in how to do it. Later, trying to update a Proceed surround-sound processor via telephone hook up, I failed miserably. Liz Jensen, who fielded my panic call to Madrigal, was extremely encouraging. "Calm down, Jim," she said. "Remember, you’re a factory-trained technician." Well, that was all the re-assurance I needed. Brushing back a wet forelock, I punched in the download code with greater serenity and tried again. The result was a perfect installation. Nowadays I regularly surf the ‘Net, looking for downloads and updates to perform. I’m even thinking to place a camcorder in the office. I might enjoy watching myself work. ...James Saxon

|

|

![[SoundStage!]](../sslogo3.gif) All Contents All ContentsCopyright © 1999 SoundStage! All Rights Reserved |

sure you know what you’re

doing?" If the work seems bogged down, I suggest shortcuts, such as, "Why

don’ t we plug it in and see where the smoke comes from?" If the technician asks

to see schematics or a service manual (often unavailable), I cover myself with

indignation, "Schematics? You don’t need no stinkin’ schematics." My

pleasure is total when he finds the source of a problem and exclaims, "Aja"

which in Spanish sounds like "A-ha," and not "Asia."

sure you know what you’re

doing?" If the work seems bogged down, I suggest shortcuts, such as, "Why

don’ t we plug it in and see where the smoke comes from?" If the technician asks

to see schematics or a service manual (often unavailable), I cover myself with

indignation, "Schematics? You don’t need no stinkin’ schematics." My

pleasure is total when he finds the source of a problem and exclaims, "Aja"

which in Spanish sounds like "A-ha," and not "Asia."