December 2000

The Ghostdance referred to in the album title and the religious cult that grew around it has clouded roots, as is the truly unfortunate case with so many things about the original Americans. What can be fairly determined is that it was begun between about 1867 and 1870, probably in northern California or Nevada, by Jack Wilson Wovoka, but gained its highest level of support among the plains tribes, primarily the Arapaho and the Sioux. What made it so different from other beliefs, and ultimately so threatening to white culture, were the very parts it seemed to borrow almost directly from that culture, namely a belief in a redemption of Indian culture through a messianic leader. In an attempt to complete their suppression of the Ghostdance cult and destroy it, the American military launched their first massacre at Wounded Knee, South Dakota in 1890. One hundred fifty were killed, over half of them women and children, and about 50 more were wounded. As such, the title of this album carries, to borrow from yet another culture, a heavy karmic burden. It delivers, but not as you expect. First, going against expectations, Ghostdance draws far less on Native American musicology than The Red Road. There are times where the "Indian" parts are impossible to see, at least if all you consider to be Indian are the occasional exotic drum beat, chant and flute. This ends up as a very good thing as it makes it harder to dismiss the work as "world music" and thus something we can either ignore as provincial, or if we do pay it attention, to focus solely on the unique wrapping. Without a high-gloss coat, the structure and lyrics are laid bare, and what we see is a strength of spirit, a beauty and a compassion that only true belief can create. Second, while Miller speaks as a Native American, using mythology that is firmly grounded in his roots, even more so, he speaks as a father, a man, and a human, using lessons that are drawn from the unique details of his own life but speak of universal themes. Thus the album is less a treatise on the Ghostdance cult, the Dakotas of 1890 or Wounded Knee in the 1990s and more an examination of the human soul and of the Ghostdance with which we each must find harmony. From "The Reason," a song of support and parting to his daughter, to "Every Mountain I Climb," a quiet anthem of vision and purpose, and on to the closing song, "The Sun Is Gonna Rise," which offers hope in the midst of the struggle of "good and evil fighting for your soul," Miller offers calm, sensitive, passionate and caring words of compassion. In all, Ghostdance is an album of beauty and tranquillity, and in these it deserves a wide and deep audience. GO BACK TO: |

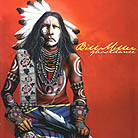

Bill Miller - Ghostdance

Bill Miller - Ghostdance![[Reviewed on CD]](../format/regcd.gif) Bill

Miller, one of several Native American musical artists to break through to a larger

audience in the ‘90s, had his initial success with his 1993 Native American/folk

masterpiece, The Red Road. A stunning combination of Native American drum

ceremonies, folk and country musicians, an uncompromising lyrical stance and a voice that

is honest and achingly beautiful, The Red Road was a critical and artistic, if

not quite commercial, smash. In early 1999, in spite of several superb follow-up efforts,

the music business being what it is, Miller found himself without a label, so his most

recent work, Ghostdance, was self-released. Later that year it was honored five

times at the Native American Music Awards. That brought the album to the attention of

Vanguard Records, who have released it nationally as well as re-releasing the three albums

Miller recorded between The Red Road and Ghostdance.

Bill

Miller, one of several Native American musical artists to break through to a larger

audience in the ‘90s, had his initial success with his 1993 Native American/folk

masterpiece, The Red Road. A stunning combination of Native American drum

ceremonies, folk and country musicians, an uncompromising lyrical stance and a voice that

is honest and achingly beautiful, The Red Road was a critical and artistic, if

not quite commercial, smash. In early 1999, in spite of several superb follow-up efforts,

the music business being what it is, Miller found himself without a label, so his most

recent work, Ghostdance, was self-released. Later that year it was honored five

times at the Native American Music Awards. That brought the album to the attention of

Vanguard Records, who have released it nationally as well as re-releasing the three albums

Miller recorded between The Red Road and Ghostdance.