November 1999

The terrible siege of Sarajevo became witness to a weapon of a different and infinitely nobler kind. Amidst the remote-controlled mass mayhem of laser-guided missiles and sniper artillery, a solitary man cut a memorable, nearly symbolic figure in the central plaza and soon became known as The Cellist of Sarajevo. To the daily accompaniment of live shelling, he defiantly dared to play his instrument, vexing international reporters who observed such foolhardiness from a safer distance. At great personal risk, Vedran Smailovic’s political activism was a reminder to himself and those listening and taking note -- emotional resistance matters. Touched deeply by the senseless killing of 22 hungry civilians who had waited for hours in a line to a bread shop just the previous afternoon, he had to uncork his dismay and purge it like poison from his soul. He did this in the only way he knew how. He played his beloved cello with all the intensity he could muster, for 22 days in a row, one day for each bread-queue victim, as though this individual act could, in some unfathomable way, ease the rampant suffering while protesting the madness with an articulate gesture of possible self-sacrifice. His well-publicized musical activism has seen Vedran Smailovic perform in many troubled places and links him with the other compatriots on this recording. Troubadour Tommy Sands, lifelong inhabitant of Ireland’s northern mountains, has always taken his music to the streets. His 1985 song "There Were Roses" has become a classic and epitomizes his ongoing commitment and direct political involvement in the peace efforts towards an end to the Belfast conflict. "Beyond the Shadows" followed suit in 1992. Three years later, the album The Hearts a Wonder predated, in one song, the common ground between the words and voice of Pete Seeger and the heartfelt cello of Smailovic that is explored more fully on Sarajevo - Belfast. Joan Baez joins in the opening "Ode to Sarajevo" as the fourth musician-activist of international renown. The gravity of the subject matter and its participants nearly precludes a critical evaluation of the music at hand. But it is only fair to note that the average listener can hardly relate to the simple, anthem-like songs and melodies with the kind of burning intensity and personal recall that comes as a natural reflex to those who have personally experienced war, devastation and religious enmity. Baptized by such fire, they will relive emotionally drenched memories to the sounds of this music. But those safely distanced and surrounded by the cozy confines of their untouched lives will assume a more abstracted mien that instantly turns into a liability: in its wake follows the inclination for undue criticism over matters of technique, performance or compositional substance. Emotional distance notices wrinkles and sunspots. An intimate embrace and cognition only beget a merger and tears. The album under review is then one of two things: either a very profound translation into the psychic space of the performers which becomes an actual event, a documentary soundtrack and, upon reflection, a testament to the healing power of music and the difference an individual can make; or, sacrilegious as it may ring, merely a fine performance by a few musicians named Vedran, Tommy, Pete, Joan and others. Imagine actual church bells, the sound of sniper fire, rain, crying children. Then a cello intoning a melancholy waltz about which you learn that Archduke Ferdinand danced to just minutes before his assassination in 1914, which sparked WW I -- the mere mention of this connection adds poignancy to a simple melody far beyond notes, vibrato or sound effects. Then there is Albinoni’s Adagio, which Vedran found himself playing, in a spontaneous and altered version, in the aftermath of the terrible burning of Sarajevo’s National Library in 1992. Afterwards friends coerced him into repeat performances, to which he agreed only because he couldn’t refuse the realization that his playing affected those listening in deep, meaningful and healing ways. Here it is now, recorded in all the dark, sad and mysterious splendor of the unique condensed form that happened upon The Cellist of Sarajevo those years ago. Like the Celtic Bards of old, the Irish Cat Stevens voice of Tommy Sands leads the ode "Where Have All the Flowers Gone" and is answered in the higher register by the well-loved Dolores Keane. On "The Music for Healing," Sands is joined by Pete Seeger in what has become a veritable new anthem in a long tradition of Irish laments. "Bembasa," like the eponymous river, is an old Sephardic song of Jewish expatriates who settled in Bosnia, and the mournful cello against the backdrop of running water transports the listener into the tortured landscape of this European region that has been the center of so much recent tragedy. I consider it mandatory that anyone listening to Sarajevo - Belfast first read the liner notes cover-to-cover. Wisdom quoted out of context becomes mere commonplace, or worse, trite. Following in the musical footsteps of Vedran Smailovic and his fellow musicians without knowing where they have been is missing the very essence of what makes this album truly unique and -- uniquely, even dramatically -- meaningful, raising it into a realm beyond criticism or reviewing. GO BACK TO: |

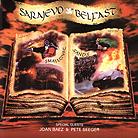

Vedran

Smailovic & Tommy Sands - Sarajevo - Belfast

Vedran

Smailovic & Tommy Sands - Sarajevo - Belfast![[Reviewed on CD]](../format/regcd.gif) War.

The mere word evokes unimaginable horrors. Sadly, our human history is an ongoing

testament to the perpetual suffering this defect in our racial psyche continues to inflict

upon us and all other beings with whom we share this planet. On the eve of the new

millennium, the annual count of violent conflicts around the globe reminds us vigilantly

that the archetype of the primitive Neanderthal clobbering his opponent to death with a

stone ax still survives in our genes. The weapons have changed but not the reactive

programming.

War.

The mere word evokes unimaginable horrors. Sadly, our human history is an ongoing

testament to the perpetual suffering this defect in our racial psyche continues to inflict

upon us and all other beings with whom we share this planet. On the eve of the new

millennium, the annual count of violent conflicts around the globe reminds us vigilantly

that the archetype of the primitive Neanderthal clobbering his opponent to death with a

stone ax still survives in our genes. The weapons have changed but not the reactive

programming.