July 1999

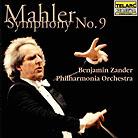

Benjamin Zander's name will doubtless be unfamiliar to most, although there has been something of a groundswell of favorable opinions gathering over the last few years. He is a conductor and teacher and -- I almost hesitate to add -- inspirational speaker who particularly enjoys working with young musicians. Zander's own Boston Philharmonic Orchestra is uniquely composed equally of amateurs, professionals and students, and their few recordings have had lavish praise heaped upon them. For my own part, I enjoyed Zander's Rite of Spring, although I was less impressed by his recording of Beethoven's Ninth. This is, unless I miss my guess, Zander's first recording with a major professional orchestra, recorded live in London's Barbican Centre. A complete Beethoven cycle is apparently next. At first sight, this set seems ungenerous, two CDs containing just under 90 minutes of music? In fact, the set contains not just two but three CDs, and it retails for the price of one. The bonus disc contains Zander discussing -- in extraordinary detail at some points -- the music and how to perform it. This is very interesting, but I should be surprised if it managed to bring the otherwise unconvinced into the fold. It is also not sufficient reason to buy this set above all others. Zander makes a number of telling points in his talk, but often seems unable to produce the required effect from the orchestra. The final climax of the movement should, as he points out, be overwhelming in its intensity, which it most definitely isn't here. And the recording, which fails to open up, is no help. The first movement is perhaps the most illustrative of my overall difficulties with this recording: in his liner note, Zander points out that "if one tries to analyze the movement in terms of traditional sonata structure, one becomes quickly confused." The problem is that Zander himself sounds uncertain as to the structural purpose of a number of the quieter episodes, and the music, while never less than affectionately phrased, seems to have no sense of direction, but meanders along aimlessly until the next climax approaches. Perhaps this ultra-episodic approach (although it is not necessarily intentional) can best (best?) be heard in the coda, which is almost static, a succession of beautifully phrased but detached events. The inner movements fare rather better, although the rustic lšndler that is the second sounds altogether too urbane and sophisticated, while the extraordinary Rondo burleske, although superbly played, fails to terrify. Furthermore, Zander begins the slow central section, which prefigures the finale, too quickly and then (at around 7:20) pulls back dramatically, as if in compensation -- but it is too much, too late. The finale may well be the most successful movement here and features some quite exquisite playing -- as witness the supernaturally quiet violins at around 5:00; their echo of the bass line is so soft as to be almost subliminal. Unfortunately, this same superhuman quietness means that the closing pages are, at any normal listening volume, totally inaudible. Although there are individual moments of great beauty in this performance, it is something of a curate's egg. The recording itself is something of a puzzle too; the first violins in particular seem to move around, or should I say back and forth? The dynamic range is huge but, as I mentioned before, doesn't open up at the big climaxes sufficiently, There is not so much a feeling of constriction as a feeling that there is no headroom left. Moreover, despite the back cover's declaration that the music was "performed live" (note the careful wording), a perusal of the liner notes shows that this disc has been stitched together from the dress rehearsal and the performance itself. While this may reap benefits in terms of reduced audience noise and the possibility of covering up orchestral flubs, it can be a dangerously two-edged sword, especially if it has led to the inconsistencies in the sound image and the overall lack of coherence in the performance evidenced here. I continue to find more of the essence of the music in many of the great recordings of the past: Bruno Walter's pioneering 1938 Vienna account (EMI and Dutton) captured live just weeks before the Anschluss and Walter's flight from the Nazis; his stereo remake from 1961, sounding better than ever in its latest Sony transfer; Otto Klemperer's stoic 1969 EMI account, made after a serious illness; Bernard Haitink's glowing Concertgebouw recording on Philips, in gorgeous late-1960s analog sound. These are probably the most obvious choices. Of more recent issues, Jesus Lopez-Cobos (also on Telarc) is better recorded, but for me no more convincing. Perhaps surprisingly, given his reputation, Boulez (DG) is no icy-cold detached observer, but summons from the Chicago SO a warm performance of fine detail and superb feeling for the architecture of the music, albeit in a relentlessly two-dimensional recording. (I have yet to hear Rattle or Dohnanyi's recordings.) But, for me, nothing quite measures up to Jascha Horenstein's towering 1966 LSO performance (Music & Arts), captured on the wing at a Promenade Concert in London's Royal Albert Hall; the recording is only adequate, the musicians are pushed to -- and past -- their limits, but the entire performance has a shattering intensity that is quite extraordinary. I know -- I was there. GO BACK TO: |

Mahler

- Symphony No. 9

Mahler

- Symphony No. 9![[Reviewed on CD]](../format/regcd.gif) Mahler's

Ninth Symphony was completed in 1910 and is the central work in his great final trilogy: Das

Lied von der Erde, the uncompleted Tenth being the other two works. There is certainly

a strong case to be made for the Ninth as the greatest symphony of the 20th century,

and there is a wealth of great performances of the Ninth already available on CD,

including two by Bruno Walter, who gave the work's first performance in 1912, after the

composer's death. So any newcomer really has to have something going for it if it is to be

successful in a crowded marketplace.

Mahler's

Ninth Symphony was completed in 1910 and is the central work in his great final trilogy: Das

Lied von der Erde, the uncompleted Tenth being the other two works. There is certainly

a strong case to be made for the Ninth as the greatest symphony of the 20th century,

and there is a wealth of great performances of the Ninth already available on CD,

including two by Bruno Walter, who gave the work's first performance in 1912, after the

composer's death. So any newcomer really has to have something going for it if it is to be

successful in a crowded marketplace.