![[SoundStage!]](../sslogo3.gif) For a Song For a SongBack-Issue Article |

|||

May 2007

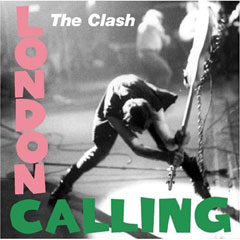

Put Your Life on the Line for Your Oppressors: Joe Strummer’s "London Calling" The lyrics to "London Calling," written by Joe Strummer of the Clash and recorded on the band’s 1979 LP of the same name, do not lay their literal meaning in your lap. But a couple of main themes and the song’s mock-martial music and indignant tone give a pretty good idea. It is well worth considering as the Clash remains on many people’s favorite-band lists decades down the road, and "London Calling," a signature song on a breakthrough album, stands out as a possible classic. Now is the time for all good men... The song’s name, a phrase repeated at the start of some three-quarters of the song’s lines, mimics the start of a phone call from the office of someone of presumed importance to the call’s recipient, indicated by identification of the caller just by his or her location -- typical of a national government, the military, or a large corporation with multiple offices. In this case, the call is from unspecified British officialdom to segments of the populace it seeks to mobilize to join in an unspecified literal or figurative war. Battle is already "come down." The people in "the faraway towns" and in "the underworld," the latter synonymous with "you boys and girls," neglected and alienated by those now demanding their help, are contacted long-distance in both space and spirit. ...To come to whose aid? "Come out of the cupboard" drives home youth’s sense of being kept in storage -- out of sight, out of mind -- till they’re wanted for service to others. Possibly worse than neglected, they’ve been treated as criminals merely by virtue of their being young. "London calling, now don’t look to us / Phony Beatlemania has bitten the dust"? The powers that be offer nothing to young folk since the last big distraction, the Beatles, faded into the background, the early "mania" over the band a thing of the past. "London calling, we ain’t got no swing / ‘Cept for the reign of that truncheon thing"? The authorities have nothing hip to offer, no music that "swings"; they intend to rely on raw power, a truncheon serving no purpose except to beat people -- another kind of "swing." Its "reign" alludes to the monarchy before democratization. There’s no longer any pretense of providing an enjoyable or meaningful life for citizens -- they must fight or be clubbed. Trivializing this with the flippant "that truncheon thing" implies there’s no moral issue -- it’s just the latest thing. The favor won’t be returned The second verse has the authorities trying additional stereotyped groups of citizens. The "imitation zone"? People who can’t think on their own and must always be shown what to do, perhaps, as the singer speaks for a government that disses them, too, in the next line: "go it alone" -- you’ve got to do your part, and don’t expect us to equip or train you. The "zombies of death"? Probably people who’ve given up or are mentally ill or chemically wasted. They are told, Just get going! But, "nodding out," they’re oblivious to their marching orders. Next, the heroin addicts. The authorities aren’t offering any "high," any respite from the unpleasantness of the war, as traditionally the Establishment has enabled soldiers or coal miners to forget each miserable day by gin or ale. You’ll have to supply yourself this time, or maybe the song is even saying methadone will be provided to those who need it -- to make them viable -- but the rest must fend for themselves. How did we come to this? In addition to the demoralizing list of factions lost to the authorities, who have long since stopped serving the people, the two slightly different refrains catalog long-warned-of calamities due to human overpopulation, technology, and unregulated enterprise. These parts of the song, and the absence of concrete images of combat or bombings, suggest possible figurative meanings of "war" and "battle" at the beginning of the song, which, in addition to a fight against a human enemy, may refer to an organized effort to fix a mess the government suddenly has decided to attend to, to evade the fact that its negligence and corruption created the mess in the first place. Nuclear winter, global warming, nuclear-reactor meltdown, drought or depleted topsoil and water, the end of oil with which to make gasoline for automobiles -- or perhaps of all of the fuels that run the "engines of capitalism": Those, in that order, are the disasters of which the singer "ha[s] no fear," according to the first refrain, because he "live[s] by the river." What the heck does that mean?! I think the idea is that London is drowning figuratively -- neither the Thames nor the ocean is filling the buildings. "London" is drowning in whatever calamity officialdom has brought about or allowed to happen, perhaps by serving the interests of the few and appeasing or abusing the rest -- neglecting the people in the countryside and alienating the youth, occasionally throwing a bone by way of pop music they can enjoy while they languish. Living by the river may be a double entendre. The singer lives near the source of the problem that is "drowning" London, and/or the singer lives from the source of the problem -- gets sustenance from it. "By" in "I live by the river" is consistent with both. The people being asked to help have long been drowning and the Establishment hasn’t cared enough to save them, and/or solving the problem the government has decided to address will disrupt many people’s lives. However bad the problem is, the people have adapted to it, and the government won’t fix dislocations wrought by their solutions. The second refrain only differs from the first in replacing "Meltdown expected" in the second line with "Engines stop running" from the third and replacing "Engines stop running" in the third line with "A nuclear era." "Meltdown expected" is the only phrase in the first refrain that is not in the second." Maybe some listeners find importance in that; I don’t see a big difference, particularly since "Meltdown expected" and "Nuclear era" refer very much to the same thing. But the mass-media term "nuclear era" for decades made the enormous dangers of government-sanctioned and -sponsored atom-splitting seem acceptable as merely one of many stages of history. Maybe the writer finds it worth working in at least in part for that reason. Disaster is OK, too: media calling The unspecific nature of so many of the song’s details isn’t vagueness or meaninglessness so much as covering a lot of territory through allusion and an assumption that the listener will know what is up. A basis for that assumption is the mediated nature of the world the song portrays -- a good many years of earth-shaking, life-threatening phenomena arising from activities sanctioned by "London" and other Western governments and reduced to media clichés that dull the mind’s perception of their alarming realities. We know what the song is talking about, and the mediated form of our understanding causes us to join in the singer’s mixture of protest, resentment, helplessness, and apathy. The negative stereotypes of the citizenry also are media clichés. "Phony Beatlemania" could not have come about without radio and television -- an iconic instance of a perfectly promoted entertainment phenomenon creating hysteria in a very short time for reasons beyond the work’s virtues. Once a media phenomenon "catches on," everyone is told they should like it. Many decide to like it without examining it. Many decide not to like it without examining it -- a protest against mediation. Given enough amusement through the media and told it is where meaning is to be found, one needn’t concern oneself with trivialities like large-scale destruction alluded to in the refrains of "London Calling." If we acted to prevent such media-diminished calamities or to minimize their impact, that would defeat the purpose of the media: to get us to hand over our money for advertised products and services, to continue attending to the media, and to stay out of the way of the Establishment. How would one act, anyway? If everyone else is watching TV, how can you solve big problems? But media-inculcated frustration and futility and the distance at which government has been able to hold the people can’t be erased merely by an announcement that the people are now needed. "London Calling" thus protests not only government’s failures, injustices, and arrogance, but also the star-maker machinery behind the popular song (as Joni Mitchell put it in "Free Man in Paris"). Particularly since the song’s comment about the media is more subtext than primary message, the Clash needn’t worry that radio will reject the song -- or the band’s body of work, which frequently attacks media and commercialism. But more to the point, media are so firmly ensconced in the catbird seat and so well versed in the chasm between feelings and actions that media help prop open that a band’s media critique would not give them pause. Appealing to an audience’s negative feelings about media is just one more media gesture to the popular interest, one more way of bolstering popularity. Rather than threaten the media, this enhances the reflection of the audience that keeps the audience coming back in the first place. That context thing Initially a protest act opening concerts for the Sex Pistols’ nihilist act, the Clash became the most influential band arising from the UK’s late-1970s punk scene. Materialism, corporatism, militarism, and bureaucracy are linked to injustice in many Clash songs. "London Calling" is representative, but by no means the only one and not necessarily the best in every way. Its succinctness, its cleverness, and the musical mixture of a martial beat with the minor chords of a monster film make it particularly artful. Songwriter-vocalist-guitarist Joe Strummer was born John Mellor, son of a British diplomat. Strummer grew up in a boarding school, quit school in his teens, and got the name Strummer from strumming "Johnny B. Goode" as a busker in the London subway. Even before the late-1950s folk-music revival in the US, performers were adopting rustic or worker personas that jibed with their repertoire better than their professor or banker or doctor or attorney parents might seem to. With mass media having put forward image sans biography, it can be quite surprising to learn the soil that nurtured some of our roots artists. Coming from one social class and championing justice for another may have a lot to be said for it. As political as an artist’s language may be and as passionately as one may express one’s views, however, entertainment remains entertainment, and organizing, power, and change remain what they are. Listening to, identifying with, and promoting artists who share our views might not have any political impact at all; it might render unto London what is London’s and keep us out of London’s hair when all concerned would benefit from our being in it. Rock bands have kept coming, some politically oriented, some not; the massive problems mentioned in "London Calling" have continued to worsen; and the world’s Londons continue allowing them to worsen. If and when they will drown, we don’t know, but with ice sheets melting and sea levels literally rising as protest songs continue to multiply, "London Calling" might turn out to be more prescient than the most ardent Clash fans would wish. I hope we’ll find our way out of the cupboard in time to make the song wrong. ...David J. Cantor |

|||

|

|||

![[SoundStage!]](../sslogo3.gif) All Contents All ContentsCopyright © 2007 SoundStage! All Rights Reserved |