![[SoundStage!]](../sslogo3.gif) For a Song For a SongBack-Issue Article |

|||

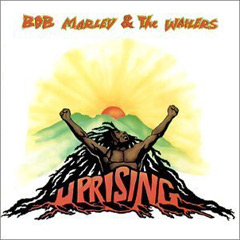

November 2005 All We Really Have: "Redemption Song" by Bob Marley

The history behind "Redemption Song," the anthem that concludes Bob Marley & The Wailers’ 1980 LP Uprising with quiet power and continues to inspire a quarter-century later, is obvious: the selling of Africans into slavery and subsequent oppression through slavery and beyond. What the song says about that history is more complex than it first appears. The song contains only two verses. The second, exhorting, "Emancipate your selves from mental slavery," repeats, becoming two-thirds of the song. So perhaps the first verse provides context, the second the main message. I think this hypothesis holds up, with the caveat that "context" does not imply a lack of substance. Details of the first verse reveal precise meanings of the second. The song’s two calls to action -- the above-mentioned and "sing these songs of freedom" -- seem vague at first, but examination reveals something broad enough to apply to a large number of people yet specific enough for each of us apply it to ourselves. Strength from adversity The beginning tells us the singer is not just the one man in a Kingston, Jamaica, recording studio in 1980 but all generations of Africans embodying the legacy of the Atlantic slave trade. Slavery had long existed before "Old pirates… / Sold I to the merchant ships" bound for the "new world." While obviously not condoning the slave trade or the atrocity of slavery, the first verse points out that some of its victims -- descendants of the original slaves -- are better off than if they had remained in Africa. "Old pirates yes they rob I"? Trading classes of societies that inhabited Africa’s coastal regions dealt with Europeans who arrived in ships to obtain goods to sell. When a slave market opened up in the "new world," some of these people acted as pirates by capturing people from farther inland, forcibly marching them to the coast, imprisoning them while awaiting "the merchant ships," and selling them. Saying "[T]hey rob I," rather than the more conventional "they stole me," hints at the fact that some of the captives had not previously been the property of another, so they were not stolen but robbed of their freedom and of their will, ego, and agency as human beings -- their status and experience as an "I." "But my hand was made strong / By the hand of the Almighty" implies that the trials and hardships that followed could not be endured without faith, and that a just deity would not let humanity-destroying piracy defeat the African people forced to leave their homelands in bondage. Beyond hope and survival "[T]he bottomless pit" refers to the depths to which African societies began to sink by taking up trade with Europeans and which have not yet been plumbed when the song was written -- or, it is safe to add, a quarter-century later. The Atlantic slave trade accelerated the deterioration of the elaborate, sophisticated cultures that had thrived in Africa for many centuries. "We forward in this generation triumphantly" contrasts "new world" slaves’ descendants with what became of free and enslaved alike in Africa after colonization. "All I ever had is songs of freedom" -- after being taken from the Africa that would decline. "I" does not specifically denote Marley, the writer, himself, whose career by 1980 had surely brought him more than just songs -- or instruments and amplifiers. Nor was Marley himself taken into slavery. And many who were did not survive the ocean crossing, while countless others died under slavery’s unbearable conditions; the hands of all slaves were not "made strong…." "I" and "my" refer collectively to all whose lineage survived. "[T]his generation" moved way beyond slavery and now has more than just "songs of freedom" -- more than something to chant for hope and solidarity. Why switch from the singular to the plural subject and back again? "[M]y hand was made strong…"; "We forward in this generation…"; "All I ever had is songs of freedom" (all emphases added). The song is about to ask "you" to "help to sing these songs of freedom" (emphasis added) -- not those of the past, which merely expressed the longing to be free and were all the collective "I" of the past "ever had," but those of today. "We" refers to descendants of slaves from the song’s time forward, free to choose the songs -- and ideas, as we’ll see -- to advance further still. Old attitude, new needs In "Emancipate your selves from mental slavery" and "None but ourselves can free our minds," "your selves" as two words possibly emphasizes the listeners’ burdensome individuality as free people as opposed to the forced anonymity of collective slavery. Adopting the imperative voice and speaking to "you" puts a moral burden on the listener that slaves did not face in their infinitely worse experience. All of us together could share the same longing for freedom and the same songs when we were slaves, the song appears to say. We were as one, albeit one enslaved and oppressed segment of humanity. Today, however, freedom has given us individual choice. Each "self" must free its own mind. Under the atrocity of slavery, which suppressed people’s humanity, we were told what to do and everyone did as everyone else did. A democratic assortment of authorities did not pull us in different directions, let alone a television-age assortment as when this song was recorded (a decade before the even-greater proliferation via the Internet). That helps explain "Have no fear for atomic energy / Cause none a them can stop the time" and "How long shall they kill our prophets / While we stand aside and look." Assassinations that have taken place and may continue -- of spiritual leaders who enable people to think freely and wisely -- should be of greater concern than even a very powerful physical danger. Even nuclear disasters, tragic as they are, do not put an end to life ("stop the time"). That happens when we choose mental slavery over continual truth-seeking. Free and strong minds empower us to overcome all threats, dangers, and disasters as the hand of the Almighty empowered the ancestors to endure slavery, so that this generation could go "forward…triumphantly." "None a them" also suggests people who indoctrinate to build opposition against one fearsome threat but are not true prophets concerned with people’s freedom and wellbeing. Seeking to block technological change is like trying to stop the passage of time. We cannot move beyond the crucial basic triumph of gaining freedom if we enslave ourselves to fear or try to take up every cause that comes down the pike. The slave’s way of thinking -- waiting for new masters to tell us what to do -- must go. Prophecy, freedom and redemption The ingenious lack of a question mark in "How long shall they kill…" creates an interesting double entendre. Is the pair of lines the question, or is "How long shall they kill our prophets" the question and "While we stand aside and look" the answer? The former is more obvious, but the latter, too, is consistent with the song as a whole. "They" will continue keeping people of African descent mentally enslaved as long as we let them destroy, with impunity, the leaders who help us stay free. "Some say" the killing of prophets merely fulfills prophecy and implicitly we need not prevent or redress it -- "We’ve got to fulfill the book." The singer disagrees. It would contradict the song’s exhortation to emancipate our selves from mental slavery, echoed in the song’s refrain. Using prophecy to justify passivity in the face of murder and injustice is one more way of choosing enslavement over emancipation and continued progress. Why isn’t it enough for songs of freedom to be songs of freedom? Why is this pair of verses called "Redemption Song," why are songs of freedom "redemption songs," and why must we all help to sing them? The ancestors sold to the merchant ships suffered -- many died. Those who survived and remained strong passed down their legacy through the generations. Freed from the bondage of slavery, we must maintain vigilance against an insidious form of tyranny in which we give ourselves over to less important matters by failing to keep up the struggle for freedom. By struggling against mental slavery and not taking our freedom for granted, we redeem the ancestors’ suffering and ensure that it was not in vain. A song for all seasons A classic is by definition a work that speaks across the generations. A quarter-century after "Redemption Song" came out on Uprising -- and while I was preparing this article -- unsought evidence attested to this song’s staying power. Despite many musicians and bands who gladly make themselves available to perform at large rallies in Washington, D.C. (and broadcast on C-SPAN), the Millions More event of October 15, 2005, marking the 10th anniversary of the 1995 Million Man March, selected Bob Marley & The Wailers’ original recording of "Redemption Song" for one of many musical interludes scheduled throughout the day. At least so far, human beings appear to be resisting mental slavery and continuing to value songs of freedom. ...David J. Cantor |

|||

|

|||

![[SoundStage!]](../sslogo3.gif) All Contents All ContentsCopyright © 2005 SoundStage! All Rights Reserved |